At the time Henslowe set about constructing his first playhouse, the Rose, the land on the southern bank of the river Thames across from the City of London, Bankside, was low-lying marshland, liable to flooding and occupied by market gardens and fishponds. Early maps may give some clues about the landscape surrounding the Rose playhouse, but were commissioned by the City livery companies whose interest was in drawing the City of London, so the detail to the south of the river is often more representative or artistic, designed to fill in the areas outside of the City. Most were drawn in London but engraved in Antwerp, and the drawers often copied each other rather than necessarily attempting a realistic depiction of what was there at the time of creation.13 In Speculum Britanniae (1593) and Civitas Londini (1600), Norden’s depictions of the land and buildings surrounding the playhouse seem to be based partly in fact and part artistry.14 Given the nature of the ground, the area was unlikely to have been as heavily wooded as Norden’s panorama, Civitas Londini (1600), suggests (fig. 71 [4.14]).15

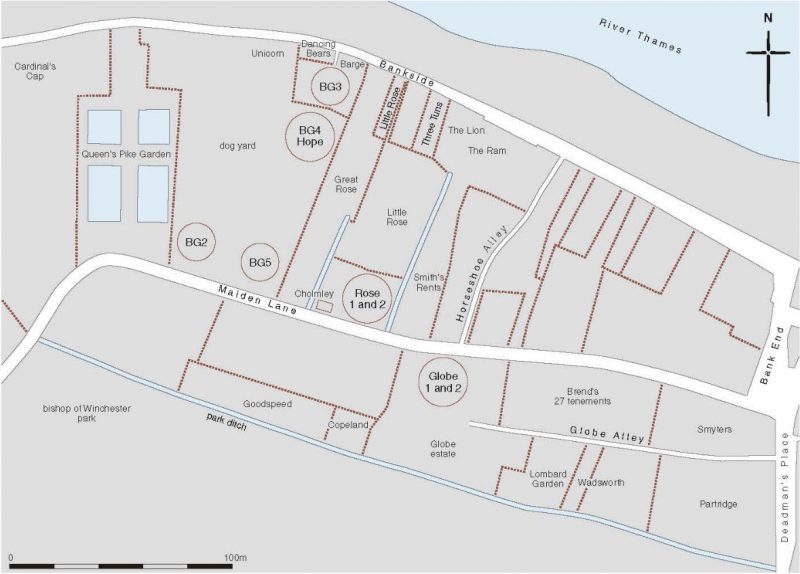

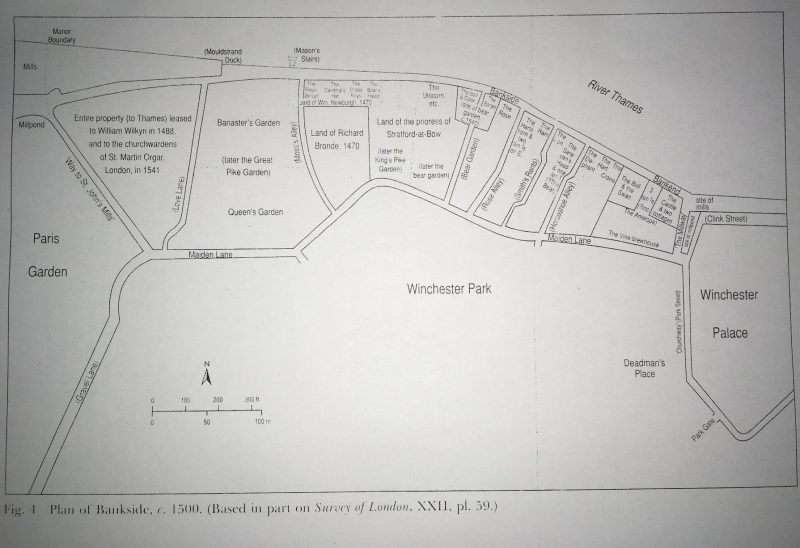

The model draws on the work of those who have attempted to chart the topography of Southwark and Bankside: figure 2 shows the ditches, land boundaries, lanes, and alleyways around the site of the Rose by the seventeenth century, drawn for MOLA by the late Chris Philpot from his researches into land tenures; and figure 3 shows a plan of Bankside c. 1500, in Martha Carlin’s Medieval Southwark, based on the Ordnance Survey and historical records.

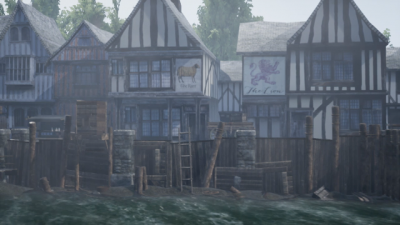

Playgoers arriving by water taxi across the river Thames would have disembarked at Bankside. Excavations of the Thames riverbank at Bankside revealed a timber wall poorly maintained and built as a hotch-potch of successive structural amendments, patching and repair from successive rebuilding and re-revetting. Archaeologists have found areas where planking from the side of a boat had been slotted between uprights to retain the ‘bank’ and form an edge to the water. Bankside was an area that was constantly flooded, which is why there was a need for all the ‘sewar’ drainage ditches.

The number of floods and subsequent repairs leave the impression that Bankside was probably untidy structurally, and probably rather unsafe.

John Stow, in his Survey of London (London, 1598), says these ‘stewhouses,’ which were usually approached by boat across the river, ‘had signes on their frontes, towardes the Thames, not hanged out, but painted on the walles, as a Boares heade, the Crosse keyes, the Gunne, the Castle, the Crane, the Cardinals Hat, the Bel, the Swanne, &c.’19

Terrarum (1572)21

Bowsher and Miller observe that ‘Elizabethan London was rather unsanitary and conveniences for solid waste were often situated on riverbanks. Such conveniences can be seen as little huts on the bankside in the Braun and Hogenberg map of 1572 (fig. 4),20 which was drawn from an earlier map in 1560, and are probably the little triangular projections that also appear on John Norden’s map, Speculum Britanniae (1593) (fig. 8 [3]).

The junction of Maiden Lane and Horse-shoe Alley © De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. To view the image using Google Cardboard, click here.

At the time the Rose playhouse was built, the only through route from Bankside to Maiden (or Maid) Lane was Horseshoe Alley (see fig. 2). Little is known about the alley. It is known that during the late winter 1593/4 and 1595/6, the player Augustine Phillips, lived with his family at the end of Horseshoe Court, later Horseshoe Alley, near Bullhead Alley (it isn’t clear which ‘end’ the alley this refers to, Bankside or Maiden Lane, as Bullhead is not marked on any surviving maps).22 He vacated by 1596/7 but takes up residency there again in 1602/3, the dwelling being part of a cluster of buildings.23

Playgoers traveling on foot across London Bridge would have made their way through the jostling streets of Southwark and Bank End, whose most striking feature was, Martha Carlin concludes, its ‘crowdedness’:

Southwark in the first half of the sixteenth century was a place of densely packed houses and teeming alleys. Its streets were choked with obstructions and traffic and its wharves with ferrymen and merchandise; churches and churchyards were bursting with the living and the dead. Houses were subdivided, gardens disappeared, and hundreds of new tenements were built by speculators. Wealthy residence could still obtain space and privacy but the poor huddled in squalid alleys, single rooms and even in stables, and threw their rubbish into public spaces—the streets, the churchyards, and the docks.18

Whether starting out from Bankside to the north or Southwark to the east, the walk towards the playhouse would have taken all playgoers along Maiden Lane, the main thoroughfare running east-west from Southwark on which the Rose was built.

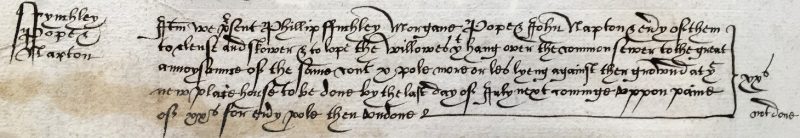

Towards the end of the sixteenth century, the Commission of Sewers noted walnut trees along the south side of Maiden Lane, and that there were willows dangerously close to their sewer ditch, which ran along the lane on the north and south sides.

In April 1588, the Commission ordered Henslowe to ‘clense and skower & to lope the willowes yt hang over the common sewer to the great annoysaunce of the same … at the new plaie house’ (fig. 5).

© London Metropolitan Archive. SKCS, vol. 18, f. 148v

The playhouse has been constructed on a parcel of land in the southern half of a larger plot, known as the Little Rose, which was itself part of the larger Rose estate, bisected by Rose Alley. Both were named after the alley and originally the Rose Inn, part of the developing riverfront ‘stews’, consisting of inns, gambling dens, and brothels.24

Rose Alley contained six small tenements in 1555, records Carlin,25 but which didn’t connect Maiden Lane to Bankside until the seventeenth century.

The junction of Maiden Lane and Rose Alley © De Montfort University, Leicester, UK To view the image using Google Cardboard, click here.

To the south of Maiden Lane lay an aristocratic hunting park which stretched west of Southwark and south from the boundary with Maiden Lane nearly to the borough boundary (fig. 6). It was related to the Bishop of Winchester’s Palace to the east, which perhaps stood in stark contrast to the prostitution and gambling district of inns, taverns and brothels to the north of Maiden Lane.

[13] The painting, ‘The Coronation Procession of Edward VI’ (1547) is the earliest representation of Bankside, seen from the north in 1547 and shows a line of trees behind (to the south of) the riverside houses running along Bankside. For maps and images depicting Southwark, Bankside and the Little Rose estate prior to the building of the playhouse, see Antony Van Den Wyngaerde’s ‘Panorama of London’ (1543) showing Southwark in the foreground (reproduced in Geraldine Mitton, ed., Maps of Old London (London: Adam & Charles Black, 1908)); G. Braun and F. Hogenberg’s ‘Civitates Orbis Terrarum’ (1572), which depicts the Bankside area with Stews, bull- and bear-baiting rings; William Smith’s ‘Panorama of London’ (1588); and the anonymous ‘Plan of Bankside on the River Thames based on an ancient survey made in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, showing the Bull and Bear Baiting’ (1809), based on a map from the seventeenth century. The engraving, ‘Plan of the City of London in the Time of Queen Elizabeth’ (1593) depicts the Southbank (reproduced in Thomas Pennant’s The History And Antiquities Of London, Vol.1. London, 1813)—it’s not clear what the circular building is; it resembles Norden’s image of ‘the play howse’ in his panorama of the same date, but its position relative to the fish ponds suggests it is in fact the bear-baiting ring. Two copies of a plan of the Little Rose estate dated to 1754 exist at Guildhall Library, MS 23737/116/38 and at Southwark Local Studies Library, Southwark Deed no. 416.

[14] For further discussion of Norden, see sections 3.1, 3.2, 4.2.2, 4.3.2, 4.4.1 and 4.91.

[15] Julian Bowsher, The Rose Theatre: An Archaeological Discovery (London: Art Books Intl. Ltd, 1989), 28.

[16] Bowsher and Miller, The Rose and the Globe, 9.

[17] Martha Carlin, Medieval Southwark (London: Hambledon Press, 1996), 37.

[18] Ibid, 58.

[19] John Stow, ‘Bridge warde without [including Southwark],’ in A Survey of London, Reprinted From the Text of 1603. Edited by C. L. Kingsford, vol. II. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 55.

[20] Bowsher and Miller, The Rose and the Globe, 132.

[22] Phillips is recorded as having played the part of Sardanapalus in The Seven Deadly Sins, Part 2 (probably related to Richard Tarlton’s play for the Queen’s Men in 1585), as part of Lord Strange’s Men c. 1590. The plot is recorded in Henslowe’s ‘Diary’ and may at one time been part of the Admirall’s Men’s repertoire (R. A. Foakes, Henslowe’s Diary, 2ndedn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002, 327). He was also one of the original Lord Chamberlain’s Men from their formation in 1594, alongside William Shakespeare, and is named among the list of the Principal Actors in the First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays. He died in 1605.

[23] Citing London Metropolitan Archives, E179/186/349, P92/SAV/245/10 and LMA, P92/SAV252/14, in Wickham, G., H. Berry, and W. Ingram, English Professional Theatre, 1530-1660 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 192, 193 and 196.

[24] Bowsher, The Rose Theatre, 17, citing W. W. Braines, The Site of the Globe Playhouse, Southwark (London County Council, 1924), 85, 90–91.

[25] Carlin, Medieval Southwark, 59, n. 187.

[26] Sir Howard Roberts and Walter Godfrey, eds. Survey of London: Volume 22, Bankside, The Parishes of St. Saviour and Christchurch Southwark (London: London County Council, 1950), 1 (Plate 1).