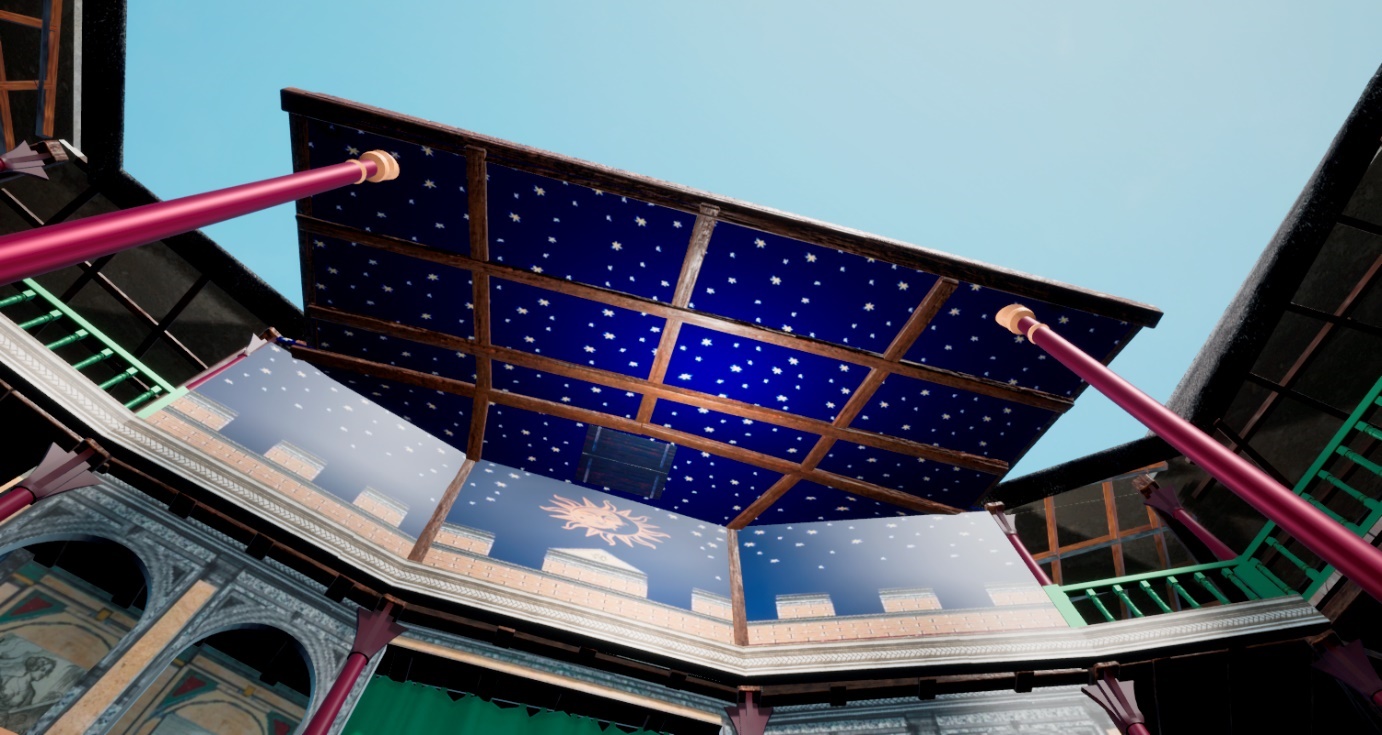

Level 3 gallery, Phase I © De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. To view the image using Google Cardboard, click here.

The other bays have been painted to look like stone and white marble, following a design similar to the screen for Worksop Manor (fig. 58 [4.11.1])

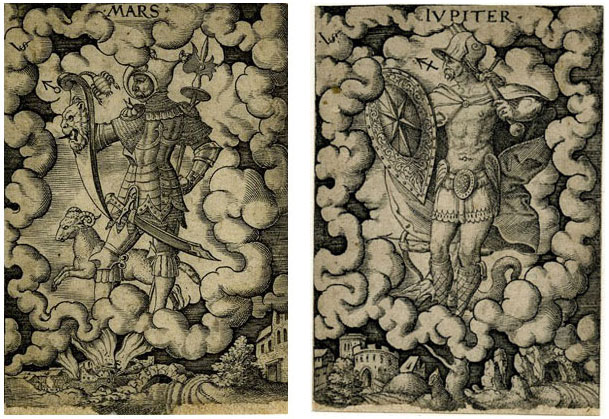

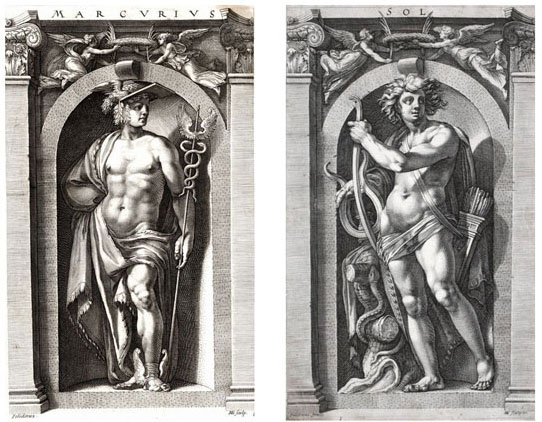

The model follows Shakespeare’s Globe’s inclusion on the frons scenae of the planetary deities, to depict the transmission of celestial influence downwards and who were understood in the Renaissance to exercise power over human life.

To the immediate left and right of the balcony is painted Virgil Solis of Nuremberg’s engravings of the Roman gods, Mars and Jupiter (fig. 66).

Again following Shakespeare’s Globe, in the arches to either side of the balcony, in grisaille, are painted depictions by Hendrik Goltzius (c. 1592) of the Roman god Marcurius [Mercury] and Sol [Apollo], from the series ‘Eight Deities’ (fig. 67).

Siobhan Keenan and Peter Davidson explain that their inclusion in the iconography of Shakespeare’s Globe is because Mercury and Apollo are ‘the “speaking out” gods, the gods of poetry and eloquence: their powers, therefore, govern the dramatic genres and contribute to the presentation of the world upon the microcosmic stage.’225

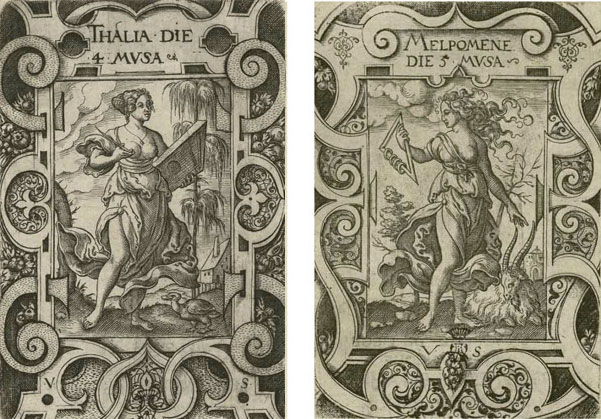

In the arches to the sides have been painted depictions of the muses (those figures who mediated between the Gods and the earth), Thalia and Melpomene, representations of comedy and tragedy respectively, by Virgil Solis (1562) (fig. 68). 226

Keenan and Davidson explain that part of the reason for the muses’ inclusion in the iconography of Shakespeare’s Globe is because ‘such figures were allegorical or emblematic in character… the dramatic muses symbolically declare the capacity of drama to represent all things under the heavens, the serious and the comic, human misfortune and human happiness.’227

The English Wager Book (1594) describes the ceiling of an Elizabethan stage: ‘Now above all was there the gay Clowdes … adorned with the heavenly firmament, and often spotted with golden teares which men call stars.’ A stage direction in an unpublished play, The Birth of Hercules (c. 1597), calls for a special arrangement to be made for the heavens: ‘Ad comoediae magnificentiam apprime conferet ut coelom Histrionium sit luna et stellis perspicue distinctum [it would especially contribute to the splendour of the play if the actors’ heavens were clearly set out with moon and stars].’

As there is no roof over the stage at the early Rose, and no canvas awning given in the model, a depiction of the night sky has been added between the arches on the third level and above on the gable front, after the gold stars on the ceiling of the Chapel at Hampton Court Palace (fig. 69a) and the ‘sky’ painted in Rycote Chapel, which depicts clouds and ‘playing card’ stars (fig. 69b) like those depicted by de Vos and Solis.228

[225] Keenan and Davidson, ‘The Iconography of the Globe,’ 152.

[226] Virgil Solis (1514-1562), The Nine Muses (1562), Université de Liège, Belgium: https://www.wittert.ulg.ac.be/fr/flori/opera/solis/solis_muses.html

[227] Keenan and Davidson, ‘The Iconography of the Globe,’ 151.

[228] Ronayne, ‘Totus Mundus Agit Histrionem,’ 139.