Assuming the Rose had three tiers, what the upper tiring house was used or what features it had isn’t known. It would have been an obvious space for storage and an office, but perhaps even an additional performance space.

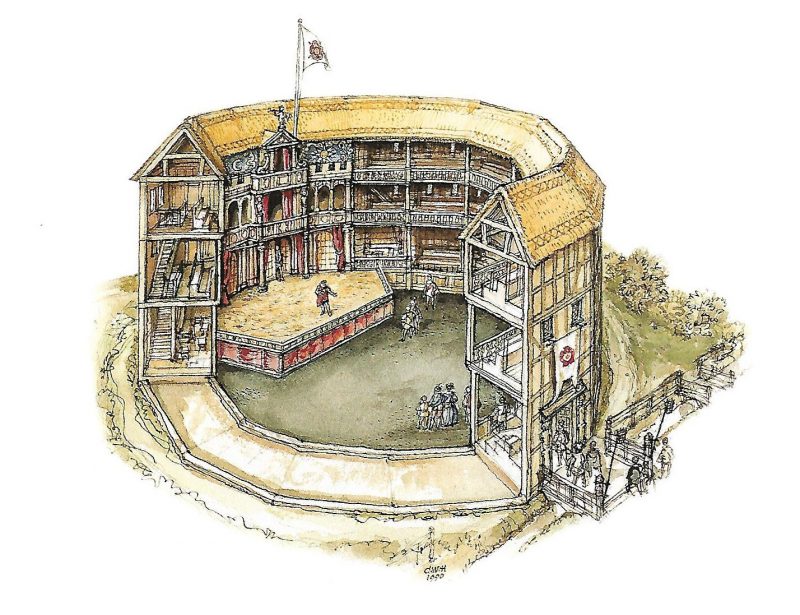

In the model, an opening has been made in the central bay to make a performance area with a central arch (following the design of the screen for Worksop Manor, see fig. 58 [4.11.1]). Although there’s no textual evidence to support its inclusion in the early Rose, the model has followed C. Walter Hodges’ inclusion of a third-tier balcony in his illustration of Phase I (see fig. 64) and his accompanying justification that ‘in some plays gods or divine messengers might appear as if in the heavens’ and which may have taken the place of the gable opening from which a trumpeter might announce the play (see 4.14), which is absent from his illustration.221

Either side are painted columns. A balustrade has also been added, painted in keeping with the rest of the balconies.

Just behind the arch hangs an imagined cloth of ‘the sun and moon,’ part of Henslowe’s inventories of 1598, so that a performer may step out in front of it to perform.222 Just what was depicted on Henslowe’s cloth is not known, but may simply have been a sun and a moon. Taking Ronayne’s assertion that the playhouse decorations was intended to be read, for the model the depiction on the cloth in the model is a little more creative.223

For the model, the image has been taken from Rosarium philosophorum sive pretiosissimum donum Dei (The Rosary of the Philosophers) (Frankfurt, 1550) (fig. 65), a sixteenth-century alchemical treatise in five parts. The term rosary in the title refers to a ‘rose garden,’ metaphoric of an anthology or collection of wise sayings which seems relevant for a playhouse. It includes the alchemical marriage, or unification, between the sun (the penetrating, sharp, solar male) and the moon (the feminine, receptive, lunar forces), represented as a King and Queen, which mix to create ‘the water of Mercury’ (a deity also depicted in the Level 3 frons scenae). The flying dove represents the spiritual force which will unite the opposing forces. The flowers are a conscious attempt by the forces to court one another.

On the cloth, the flowers have been depicted as a ‘rose’ (taken from The Grete Herball, 1526) (see fig. 14 [4.2.1]) and altered to resemble a Tudor Rose, the marriage of Stuart and Lancaster used in Elizabeth’s portraits to refer to the Tudor dynasty and the unity it brought to the realm. The rose also had religious connotations, as the medieval symbol of the Virgin Mary. It was used to allude to Elizabeth, the Virgin Queen, as the secular successor to the Virgin Mary. Elizabeth I was often presented as Cynthia, the goddess of the Moon, who was a virgin and therefore pure, promoted by Sir Walter Ralegh in his poem ‘The Ocean’s Love to Cynthia,’ in which he compared Elizabeth to the Moon.

[221] C. Walter Hodges in Bowsher, The Rose Theatre, 75–77.

[222] Malone, Historical Account of the English Stage, III, 312.

[223] Ronayne, ‘Totus Mundus Agit Histrionem,’ 123.

[224] Jaroš Griemiller of Třebsko, Rosarium Philosophorum (1578), National Library of the Czech Republic (Národní knihovna České republiky), Prague, MSS XVII.E.77, f. 19v.