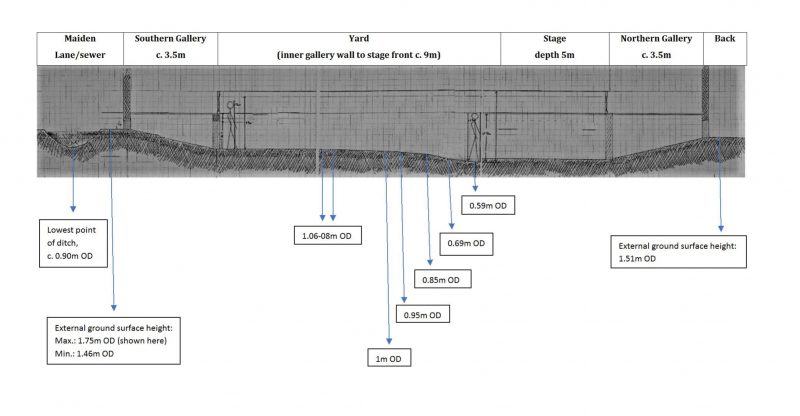

Evidence for the external surfaces around the playhouse from the excavations is patchy, and the dig ‘did not allow for a complete survey of the natural and redeposited strata across the site,’ records Bowsher and Miller.80 Nevertheless, there seem to have been local undulations and a general slope from south to north of the plot. The topographical heights recorded are:

- To the southwest [A813; see the area outlined in grey to the left of bay 4 in fig. 2, CAD drawing], the only clearly identified area of ground surface associated with the building was a redeposited clay layer at an average height of 1.73 OD (but whether it was a residual area of natural ‘high ground’ or a result of remodelling the landscape around the new Rose is not certain).

- To the southeast [B173], a graveled/metal surface, which may be contemporary with the playhouse: 1.46m OD.

- To the south [B1404], appears to be a surface pre-playhouse: 1.56 OD.

- To the west [B626], a height of 1.46 OD.

- To the north [B311], by the outer wall: 1.51 OD. Further north [B509], the cobbled surface transgressing the northern ditch and another possible surface [B107] both lay at 1.30 OD.

- To the northeast [A748], a clay deposit, which may have been contemporary with the playhouse: 0.8 OD.

- No known levels for the area northwest.

- To the east, there is some evidence of the ground surface contemporary with the playhouse (a layer of light grey course sandy with pebbles, adjacent to the revetted ditch [PKU01]): 1.52 OD.

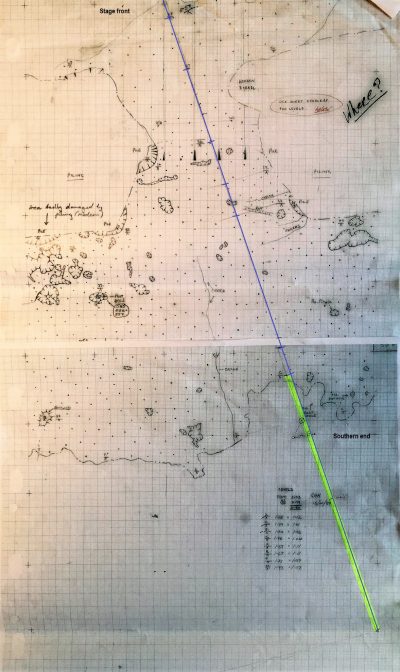

The models have been based on these ground surface heights as well as by plotting a straight line across the centre of the playhouse yard running south to north, recorded on the context sheets archived at London Archaeological Archive and Research Centre (LAARC) (fig. 31), which make it possible to draw a cross-section of the site on which the Rose playhouse was built (fig. 32).81

From these surviving sixteenth-century ground levels it is possible to conjecture the relative heights of the lower gallery, as calculated by Bowsher and Miller and on which the model has been based:

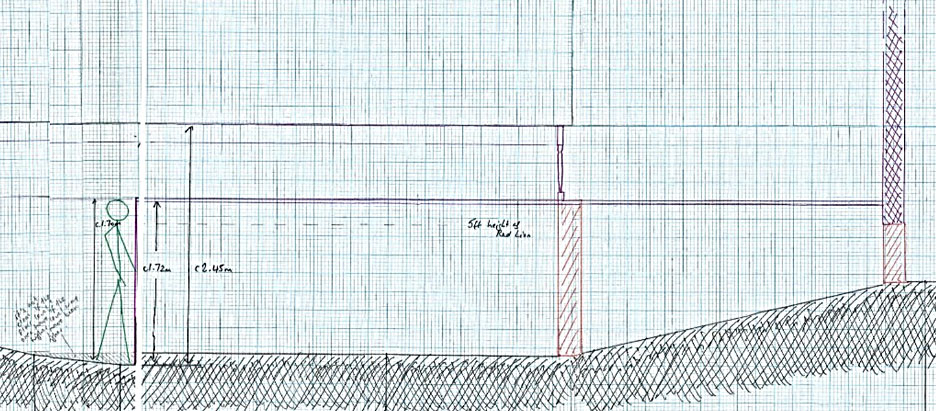

The maximum height found on the brick piers was 1.75m OD. If to this we add a 12” (0.30m) brick plinth wall [attested by the Fortune playhouse contract] it brings us to 2.05 OD. The timber cill beam over this can be conjectured at 9” (0.24m) square [attested by the Hope playhouse contract], thus bringing us to 2.29m OD. The cill beams would have been at the same level as the cross beams and floorboards of one inch (0.02m) over these would give a hypothetical gallery floor level of 2.32m OD. A baluster fragment found during the excavations was used as a basis for reconstructing those fronting the galleries at the new [Shakespeare’s] Globe. This, with handrail and jetty rail, would provide a hypothetical handrail level fronting the lower gallery of 0.05m OD. [The yard floor was raked] at an average height of 1.08m OD in its southern half but then slopes down towards the stage where it is about 0.60m OD. The slight uncertainty is caused by severe erosion on the floor surface at the front of the stage. Thus there is 2.45m (8ft) between the yard floor against the stage front and the handrail height of the lowest gallery.However, the height between the surface in the southern half of the yard and the handrail is lessened to 1.97m (6’ 6”). A reduction of 0.73m (2’ 4”) brings us to 1.72m (5’ 8”) and 1.24m (4’ 1”) below the gallery floor level. The average height of an adult male human being at this period was 5’ 7” (1.71m) and a female 5’ 2.5” (1.59m). Thus they would have stood at an average of 0.01m and 0.13m (5”) below the gallery floor against the stage, but at an average of 0.47m (1’ 6”) and 0.35m (1’ 2”) above the gallery floor level at the southern end of the yard. For the stage to have had a floor level of 2.32m OD, the same as the gallery floor, it will have been 1.70m (5’ 7”) above the yard surface at its deepest point. This was clearly above eye level for the average man. Moreover, the only documentary reference for stage height is from the Red Lion of 1567 where it was 5ft (1.52m) high. This is assumed to be the height above the level of the yard. Certainly Thomas Platter in 1599 recorded that playing was on a “raised stage” … It may be that the external wall foundations were lower that the twelve inches we have copied from later building contracts. Alternatively, the stage may have been at a lower level than the galleries, or even slightly raked towards the yard.82

Based on the relative heights of the ground levels taken from the excavation data provided by MOLA, Greenfield calculates that

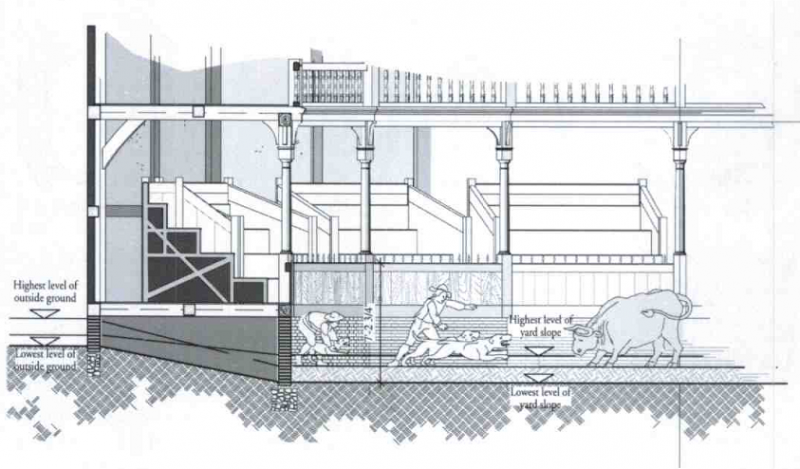

Eye height of someone seated at the front of the gallery would have been about 4’1” (1.24m) above this, making the eye height of someone sitting at the front of the gallery 9’9” (2.96m) above the yard level by the stage and respectively 8’2” (2.48m) by the southern entrance. If we assume that the balustrade on the front of the lowest gallery is two feet five inches in height, and that it was built like the one described in the Fortune [playhouse] contract, i.e., finished on both sides with solid planking and not made as open balustrade, it would have presented a wall to the yard that was over seven foot at its lowest (by the entrance [bay 1]) and nearly eight foot at its highest (by the stage) … It is an unfashionable idea, and one that we do not willingly wish to admit to, but there is the possibility that the Rose, in its original form, was based on antecedent arenas that were set up for baiting fierce animals, bears and bulls, with dogs [fig. 34, below]… My primary proposition is not that the Rose is necessarily used for baiting animals, but that the animal baiting arenas provided Henslowe with his playhouse model.83

Greenfield and Gurr proposed that ‘the first building was positioned to exploit a natural hollow in the ground,’ leading them to speculate that ‘the first building did not actually have a stage,’85 and to suggest that the development of Rose playhouse was ‘transitional, particularly in the first five years’ when its purpose of use is unknown and, ‘[i]f, as the records seem to show, there were no acting companies resident at the Rose during its first five years.’86 Bowsher points out, however, the lack of archaeological evidence for the notion that ‘the yard was built around a ‘natural hollow’ or ‘natural depression,’ because the ground at the lowest levels ‘[were] not necessarily natural strata or original surfaces.’87

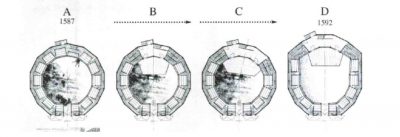

As a snapshot in time, our model at least concurs with their suggested phase C of the hypothetical development of the building (fig. 35) put forwards by Gurr and Greenfield from ‘a first building that did not actually have a stage’ through ‘a dual-purpose theatre and baiting house’ with removable trestle-stage, to a more permanent stage/playhouse at least until the building’s redevelopment in 1592.88

However, Bowsher is certain that the Rose was never dual-purpose, nor ever intended for animal baiting and has argued convincingly against Gurr and Greenfield’s thesis.90

The design of the quasi-amphitheatrical outdoor playhouses may have been influenced by the elevated galleries of the country innyards and enhanced by the space provided by the triple ranks of galleries in the animal-baiting houses, and perhaps modelled at some remove on Roman theatres.91 The design of the Rose in particular is likely to have been influenced more by the design of the Theatre playhouse in Shoreditch than the nearby bear-baiting arenas.

[80] Bowsher and Miller, The Rose and the Globe, 34–35.

[81] See also Jon Greenfield, ‘Section showing the ground levels in 1587,’ in Greenfield and Gurr, ‘The Rose Theatre, London,’ 337; and the diagram chowing the relative heights of the lower gallery in Bowsher and Miller, The Rose and the Globe, 89.

[82] Bowsher, ‘The Rose and its Stages,’ 41.

[83] Greenfield, ‘Reconstructing the Rose,’ 28 and 30. For elaboration on this argument, see Gurr, ‘New Questions about the Rose,’ n.p.; Greenfield and Gurr, ‘The Rose Theatre, London,’ 330–40; and Andrew Gurr, ‘Bears and Players: Philip Henslowe’s Double Acts,’ Shakespeare Bulletin 22:4 (Winter 2004), 31–41.

[84] Greenfield and Gurr, ‘The Rose Theatre, London,’ 336.

[85] Ibid, 335.

[86] Greenfield, ‘Reconstructing the Rose,’ 24. See also Andrew Gurr, The Shakespearian Stage 1574–1642, 3rd edn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 124.

[87] Bowsher, ‘The Rose and its Stages,’ 41.

[88] Greenfield and Gurr, ‘The Rose Theatre, London,’ 335–36.

[89] Ibid, 335.

[90] See Bowsher, ‘The Rose and its Stages,’ 44–47. Bowsher argues that the ‘deed of partnership’ calls for the erection of a ‘playe howsse,’ a term not readily translatable to a baiting arena, and that the phrase ‘or otherwysse howsoever’ in the contract, which Gurr and Greenfield argue may suggest activities like animal baiting, is ‘a common legal term found in many contracts intended to embrace any ambiguity’ (45). The ‘deed of partnership’ is, he points out, very clear in the building’s purpose; they would ‘permitte suche personne and personnes players to use exersyse & play in the said playe house’; ‘any playe or playes that shallbe showen or played there or otherwysse howsoever’; and the only activities specified within the building were to be plays or ‘enter-ludes,’ which might also encompass music or dancing (Foakes, Henslowe’s Diary, 304–6).