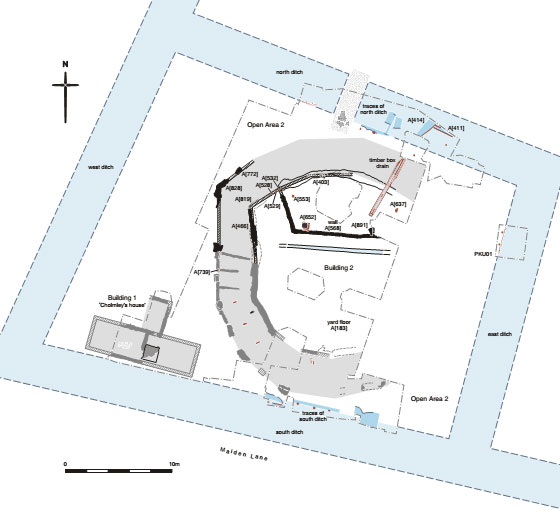

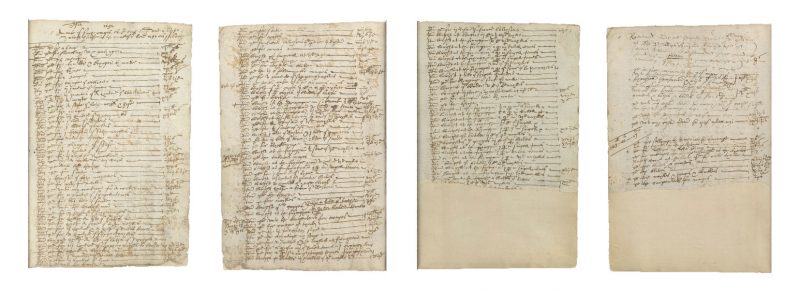

In February 1592, Henslowe records in his accounts book (his ‘Diary,’ MSS VII, ff. 4r–5v) ‘A nott of suche c[h]arges as I have layd owt a bowte my playe howsse in the yeare of or lord 1592.’234 The work totalled c. £105, and includes payments for, for example, ‘wharfyng,’ ‘tymber,’ ‘lyme,’ ‘deall bordes,’ ‘peny naylles,’ ‘rafters,’ ‘quarters,’ ‘lathe naylles,’ ‘sand,’ ‘fore powlles,’ ‘a mast’ and payment of wages to ‘the thecher’ [thatcher], ‘for brycklaynge’ and ‘workmen’ (see fig. 75).235

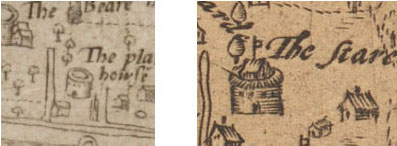

Norden’s map printed in 1600 appears to show that changes have taken place since his first edition was printed and published in 1593 (but drawn sometime earlier):

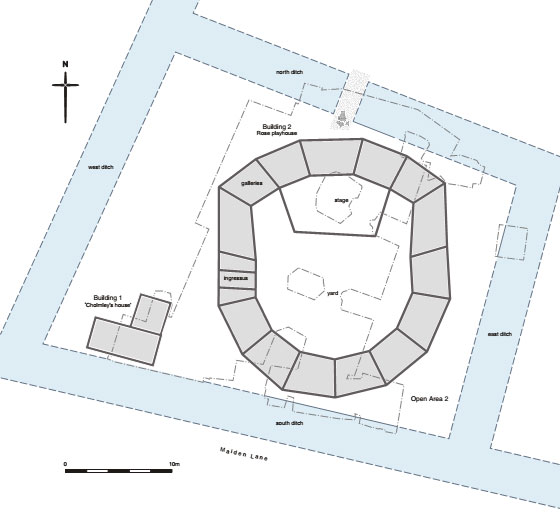

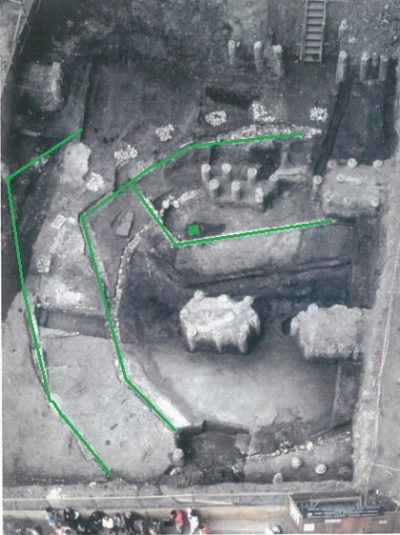

It wasn’t until the playhouse was excavated in 1988/9 that it was possible to see what all this expenditure might have been for: to add a roof over the stage, which meant extending the galleries to the north to help accommodate sightlines;236 to add capacity to the yard and galleries; 237 to add or extend more elitist audience areas such as Gentlemen’s and ‘Lords room’; to allow for new staging arrangements; 238 and to enlarge the tiring house.239

In his unpublished doctoral thesis, Yuanbo Mao argues that ‘Henslowe meant Phase I and Phase II to function differently, with Phase I, like its predecessors [the Theatre and the Curtain playhouses], designed to serve as an alternative inn-yard or inn-yard-like, rentable playhouse, whereas Phase II, like many of its followers [the Globe, the Fortune and the Hope playhouses], a repertory playhouse.’ 240 To support the former he cites the clause in the ‘deed of partnership’ in which is specified that as owners of the playhouse Henslowe and Cholmley were ‘ioyntly to appoynte and permitte suche personne and personnes players to vse exersyse & playe in the saide playe howse’ (fig. 7 [3]).241 That the modification of the playhouse in 1591/2 was primarily to alter the stage and tiring house to accommodate more permanent playing companies may be supported by the arrival of Lord Strange’s Men, led by Edward Alleyn, and who may have influenced the playhouses redesign.242

Copyrights Ltd./The Rose Theatre Trust

The alterations to the superstructure of Phase I involved dismantling of the northern half of the building and rebuilding on new foundations, a process needing great care because most of the timber framework would very probably have been reused and re-erected in the new scheme.243

The ground level between the original gallery walls to the side of the stage was substantially raised, and shallow trenches for the new inner walls appear at this level in the excavations.

Renovations must have been completed sometime before 19 February 1592 when Lord Strange’s Men began playing at the Rose, and may have taken place sometime in the previous year. 245

Fig. 78: Diagrams showing the relative positions of the excavated remains of the Phase II playhouse and the altered layout of the bays © MOLA244

Concerning decoration, items paid out by Henslowe, recorded in his diary in 1592 (MSS VII f. 4v), include:

Itm pd for turned ballyesters ijd qr A pece,ij dossen246………Iiijs vjd

Itm pd for ij dossen of turned ballysters……………………………..iiijs

Itm pd for payntinge my stage247…………………………………..…..xjs

Other notable entries (MS VII f. 5v) give:

Pd for sellynge of the Rome over the tyerhowsse ……….……..xs

Pd for selling my Lords Rome……………………………………….….xiiijs

Pd for makeing the penthowsse shed at the tyering

howsse doore as foloweth pd for owld tymber………………….xs

On 23 March 1591, Henslowe records payment ‘unto the paynters’ of twenty-six shillings, the equivalent of 19.5 days’ work for one labourer, assuming a wage of 16d a day.248

Between 14 March and 22 April (Easter Monday) 1595, the Rose was closed for five weeks during Lent to be painted and repaired at a further cost of £105 19s. Henslowe records ‘A nott what I have layd owt abowt my playhowsse ffor payntynge & doinge it abowt w[i]th ealme bordes & other Repracyones249 as followeth 1595 in lent’ (MS VII f. 2v), , and includes nine payments to ‘the paynter’ amounting in all to 96 shillings (or £4 10s):

Itm geven the paynter in earnest………………………………..xxs

Itm geven the paynter more………………………………………..xs

Itm geven more unto the paynter………………………………..xs

Itm pd the paynter………………………………………………………vs

Itm pd the paynter………………………………………………………vjs

Itm pd the paynter……………………………………………………….iiijs

Itm pd the paynter………………………………………………………vs

Itm pd the paynter In fulle……………………………………………xvjs

The accompanying list, not given here, includes payments for the carpentry materials associated with ‘furnishing’ trades: some plastering, perhaps of partitions; some boxing out with elm boards; a hinged element; a door, shutter or other such device.250

The contract between Henlsowe, Edward Alleyn and the carpenter Peter Street for the erection of the Fortune playhouse (fig. 16 [4.2.2]) includes a clause so that ‘the said Peeter Streete shall not be chardged w[i]th anie manner of pay[ntin]ge in or aboute the said fframe howse or Stadge or anie p[ar]te thereof nor Rendringe the walls w[i]thin.’251 It seems the same was also true of the renovations to the Rose in 1591/2.

Frustratingly, Henslowe doesn’t record just what was being painted. Whitewash on plaster was commonly employed on external as well as internal walls if the plaster finish alone was not considered sufficient, and it may be that for the playhouses the wooden beams were also whitened over (see 4.2).

Salzman notes from the surviving payments to painters, that in the thirteenth century ‘a common form of decoration was to mark out the whitewashed walls, usually with red paint, in blocks to resemble masonry,’ the blocks then decorated with a simple device, such as a rose.252 He also notes the practice of adding colour to the washes to make the walls red or yellow, along with painting the beams and posts of halls, and applying techniques such as painting wood to resemble marble or decorating walls with gold stars. Further to general techniques was the painting of elaborate pictures including symbolic, mythological and allegorical images, such as pictorial representations of stories from the Bible.253 The painter might also have been employed to create painted cloths (see 4.11.1).

Such relatively large sums paid by Henslowe to the painter were less likely to be remuneration for artistic merit and more likely inclusive of the cost of tools and materials as well as time spent in preparing the oils and pigments necessary to do the job, although these expenses are not expressly recorded by Henslowe.254 Gold leaf and blue pigment were dearest, with ‘bice,’ a cobalt blue, and indigo generally employed in decoration; for green, ‘verdigris’ was employed, but could also be achieved by mixing blue and yellow; different types of red could be achieved using ‘ochre’ or, brighter still, ‘red lead’ paint; black was made from charcoal, ‘lamp-black,’ or soot; white lead or ‘cerise’ was in common use; and earthy yellows and browns could be gained from ‘Spanish brown’ or ‘umber.’ Whilst the painting itself was probably free-hand, time spent preparing and marking up the walls may also have been included in the costs.255

Dated 4 June 1595, payment is listed in Henslowe’s accounts of £7 2s made ‘for carpenters worke & mackinge the throne In the hevens,’ a reference to the construction of machinery by which a chair can be winched up and down from the trap in the heavens roof above the stage.

[234] See Introduction, note 1.

[235] See Foakes, Henslowe’s Diary, 9–13. Whilst there was a flagpole common to playhouses, Julian Bowsher suggests that the ‘mast’ purchased by Henslowe on this occasion was more likely used as a ‘ginpole,’ a support for the lifting tackle (i.e., a rudimentary crane) (Bowsher and Miller, The Rose and the Globe, 54–55).

[236] Bowsher points out that ‘[t]he widening of the gallery walls either side of the new stage was made so that sightlines from the upper galleries to the stage below the new roof could be maintained’ (‘The Rose and its Stages,’ 47).

[237] The change in the galleries’ capacity between the two phases is more difficult to ascertain. Practical experiments conducted by MOLA on the capacity of the Phase II yard estimated a 39% increased capacity on average between the two phases (Bowsher and Miller, The Rose and the Globe, 157). Gurr estimates that the overall effect of yard and gallery enlargement could have increased audience capacity by around 500 (Andrew Gurr, Shakespeare’s Opposites: The Admiral’s Company 1594–1625 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 125), although Bowsher suggests this is an underestimate; experiments have suggested that the size of the yard might accommodate 550 people loosely packed, and 740 tightly packed (Bowsher, The Rose Theatre, 59). As far as increased capacity in the galleries in Rose Phase II is concerned, Bowsher concludes that ‘analysis shows that little extra space was gained for an audience’ (Bowsher, ‘The Rose and its Stages,’ 47). Fig. 78 showing the outline of the Phase II Rose certainly suggests increased capacity, although we have no way of knowing what the architectural space itself was used for, since very little of the superstructure above ground survives. Wickham et al. hypothesise that the northward extension was a way to enlarge capacity (Wickham et al., English Professional Theatre, 1530–1660, 422) and S. P. Cerasano conjectures that the enlarging of the space was a direct response to the playhouse’s success (Cerasano, ‘Philip Henslowe (c. 1555–1616),’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, Jan 2008). The extent to which the increase in capacity may have justified for Henslowe the expense and extent of the structural changes can’t be known for certain. It seems reasonable to assert that such as business man as Henslowe would have been looking to increase capacity in his redesign of the Rose, even if the motivation also included other rationale such as a roof over the stage, for example; the increasing popularity of playgoing in London mixed with the overall increase in population during the 1580s and 1590s would certainly have provided motivation.

[238] Bowsher concludes that the primary objective of the 1592 modification was ‘to enhance the stage by providing greater dramatic potential—which may indeed have attracted larger audiences’ (Bowsher, ‘The Rose and its Stages,’ 47). How far this is true is questionable: the ‘throne in the heavens’ wasn’t added until 1595 and may have been a later innovation not considered at the time of the restructuring; and although a trap appears to have been added in Phase II, one might easily have been accommodated in Phase I. There was only a small increase in the square footage of the Phase II stage.

[239] C. Walter Hodges has conjectured that ‘It is very likely that the need to enlarge here [the tiring house] was a major factor in the later decision to enlarge the whole theatre’ (C. Walter Hodges, in Bowsher, The Rose Theatre, 75), although it is not known how many bays the Phase II tiring house occupied or whether the construction of the tiring house was expanded beyond the main gallery superstructure.

[240] Yuanbo Mao, ‘The Rose Playhouse in Context,’ Doctoral Thesis submitted to the Faculty of English Language and Literature of the University of Oxford (Oxford University Research Archive, 2016), 30 [unpublished].

[241] Foakes, Henslowe’s Diary, 305–6.

[242] See Introduction, note 1.

[243] Bowsher and Miller, The Rose and the Globe, 56.

[244] Ibid, 58, 125.

[245] See Introduction, note 1.

[246] I.e., two-pence farthing each for two dozen balusters.

[247] It’s possible the payment records decorating the tiring-house façade as well as, or instead of, just the stage boards themselves. Chambers documents two obscure references to ‘paintid stage’ (1579) and a ‘painted hevenes’ (1629) (see Chambers, The Elizabethan Stage, II, 530 n.2 and 546 n.2).

[248] Jan Luiten van Zanden, ‘Wages and the cost of living in Southern England (London) 1450–1700,’ International Institute of Social History, 2002: https://iisg.amsterdam/en/blog/research/projects/hpw/datafiles?back-link=1 [accessed 26 October 2017].

[249] I.e., reparation: an act of replacing or fixing parts of an object or structure in order to keep it in repair, or of restoring an object or structure to good condition by making repairs (OED).

[250] Bowsher and Miller, The Rose and the Globe, 64.

[251] Foakes, Henslowe’s Diary, 308 (Muniment 22).

[252] Salzman, Building in England Down to 1540, 158.

[253] For further information on whitewashing and painting techniques, see Salzman, Building in England Down to 1540, 157–60.

[254] For the purpose of cost and expediency, the images used for the both models have been taken directly from paintings, woodcuts, etchings, and illustrations rather than necessarily being re-rendered into something less skilful. Highly skilled workmanship can be seen painted onto the walls and hanging cloths of Tudor houses of the nobility in England by craftsman so it is not too fanciful to assume that skilled painters were also employed to decorate London’s playhouses. The interior decoration was what helped transform the spectator from the everyday into the fantastical world of the drama and it is not unreasonable to conclude that effort, skill, and expense was employed in achieving something awe inspiring as attested in the written accounts of visitors to London’s playhouses.

[255] For further information on the costs of painting and painters, see Salzman, Building in England Down to 1540, 160–72.