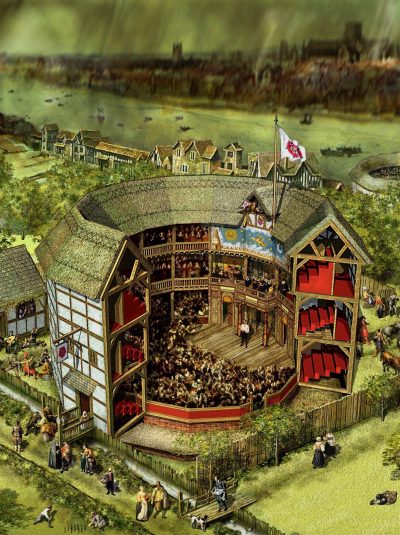

William Dudley exposes the timber frame in his illustration of the early Rose (fig. 15), as does the illustration by C. Walter Hodges (fig. 64 [4.13.2] and fig. 92 [5.8.5]).

The model of Phase I likewise shows the exterior of the first phase of the Rose playhouse as a visible timber frame.

However, it is possible that the wooden frames of London’s playhouses were whitewashed or the outer walls completely plastered over and painted to make them look more like a solid or stone building: in Tudor England, ‘Timbering was frequently plastered or lime-washed over (exposed and black-painted timbers being largely a Victorian fashion).’41

Edward Alleyn to erect for the sum of £440 a ‘new howse and stadge for a Plaiehowse [the Fortune] . . . nere Golding Lane,’ to have the same dimensions, as given, as the Globe Theatre, Jan. 8, 1599/1600, with acquittances on the verso dated Jan. 8, 1599–June 11, 1600

© David Cooper. With kind permission of the Governors of Dulwich College

The contract for Henslowe’s later Fortune playhouse (fig. 16) stipulates that ‘all the saide fframe and the [external] Stairecases thereof to be sufficyently enclosed w[i]thoute with lathe[,] lyme & haire.’42 Whether this was the case for the Rose as well is not stipulated in the ‘deed of partnership,’ which included no references to the design or construction of the playhouse.

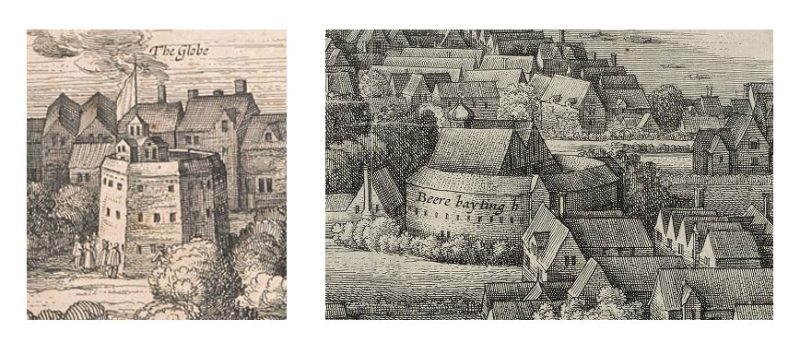

None of the depictions of the Rose by Norden show an obvious timber frame (see fig. 53 [4.9.1] and fig. 71 [4.14]), and depictions of the first (fig. 17) and second Globe (fig. 18) playhouse appear to suggest a solid or plastered exterior, which lead John Ronayne to conclude ‘it must have been rendered.’43

(right) Fig. 18: Detail, the second Globe playhouse (mislabelled ‘Beere bayting’) in Wenceslas Hollar’s ‘Long View of London from Bankside’ (drawn c. 1630, publ. 1647)

Ronayne suggests that ‘as playgoers approached an Elizabethan theatre they would have seen the high white walls (plaster over half-timbering) suggesting perhaps some grave and substantial Roman temple or arena. But once through the doors, they would have entered a world of imagination and possibility far removed from the lath and plaster familiar from everyday life.’44 He goes on to argue that evidence of lath nail holes and nails detected on sixteenth-century buildings is further proof of exterior render, and he gives examples of payments made to tradespeople to lath and plaster and paint ‘as stone’ the exterior of contemporary buildings.

Andrew Gurr’s view is that ‘all lath-and-plaster walls would have been painted, or plastered, to conceal the woodwork, leaving a white cover. That however, would still show up the lines of the framing timbers, at least in outline. The experiments that Peter McCurdy and I did [in designing and building the reconstructed Shakespeare’s Globe in London] suggest that the timber frames would always have been apparent, even after a thorough whitewashing.’45

However, much of the evidence for plastering the external walls of London’s playhouses comes later than Phase I of the Rose and it is at least possible that the frame was left uncovered.

[41] English Heritage, ‘Tudors: Architecture–the Middling Sort’: https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/story-of-england/tudors/architecture/ [accessed 22 July 2017].

[42] Foakes, Henslowe’s Diary, 308 (Muniment 22).

[43] John Ronayne, ‘Style,’ in ‘The shape of the Globe’: Report on the seminar held at Pentagram Limited, London by the International Shakespeare’s Globe Centre (ISGC) on 29 March 1983, eds by Andrew Gurr, John Orrell, and John Ronayne, The Renaissance Drama Newsletter Supplements 1 (Coventry: University of Warwick Graduate School of Renaissance Studies, 1983), 23. In discussing the exterior for the reconstructed Shakespeare’s Globe in London, Roynayne suggests: ‘The question whether the rendering should be complete or the timber should be exposed enough to breath is less significant than the conclusion that a magpie black and white half-timbering is not acceptable.’ Gabriel Egan notes that later Ronayne was to argue the opposite: ‘As our reconstruction is the first major timber-framed building in the capital since the [great] Fire, our decision, on balance, was to expose the structure of what is a rare sight in London, rather than cover it up as the Elizabethans may have done, taking for granted the frameworked appearance. For them, outer rendering was grander. For us, half timbering is more generally evocative.’ (Ronayne, ‘Totus Mundus Agit Histrionem,’ 122; Gabriel Egan, ‘Reconstructions of the Globe: A Retrospective,’ Shakespeare Survey 52, ed. Stanley Wells (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 1–16).

[44] John Ronayne, ‘Totus Mundus Agit Histrionem: The Interior Decoration Scheme of the Bankside Globe,’ in Shakespeare’s Globe Rebuilt, eds. Ronnie Mulryne and Margaret Shewring (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 121.

[45] Personal correspondence by email, 11 August 2016.