There were buildings with or without jutties (also called jetties) in almost equal number in the London area by 1576. However, within a few years they were to become illegal within the city, although not applicable to the Rose, presumably, which lay in the Liberty of the Clink and therefore outside of the area of Southwark which had, since 1550, been incorporated in to the City as ‘The Ward of Bridge Without.’

A drip line in the yard surface of the early Rose playhouse, which lay 0.50m from the inner wall and was 0.50m wide, suggests that rainwater from unguttered eaves was perhaps enhanced by jutties (fig. 30). However, analysis of the various dimensions of the drip lines at both the Rose and a similar drip line at the reconstructed Globe in London suggest that any projection of the eaves was minimal.

Like Greenfield, Gurr wonders whether this means there were two rather than three galleries (see 4.4.1): ‘The erosion trench cut into the mortar surface of the yard by the constant dripping of water from the thatch of the gallery roof is rather closer to the inner gallery walls of the Rose than the one now marked in the new Globe’s yard. The Globe’s three galleries include two jutties or extensions into the yard from the second and third levels of gallery. The erosion trench at the Rose, being nearer the inner gallery wall, may show the position of thatch covering only two levels of galleries, with a single jutty.’73 The projection of some 0.74m to the vertical fall of the centre of the drip line suggests that either the Rose was of three storeys with a minimal eaves projection, or that it had three storeys only, of which one was juttied.74

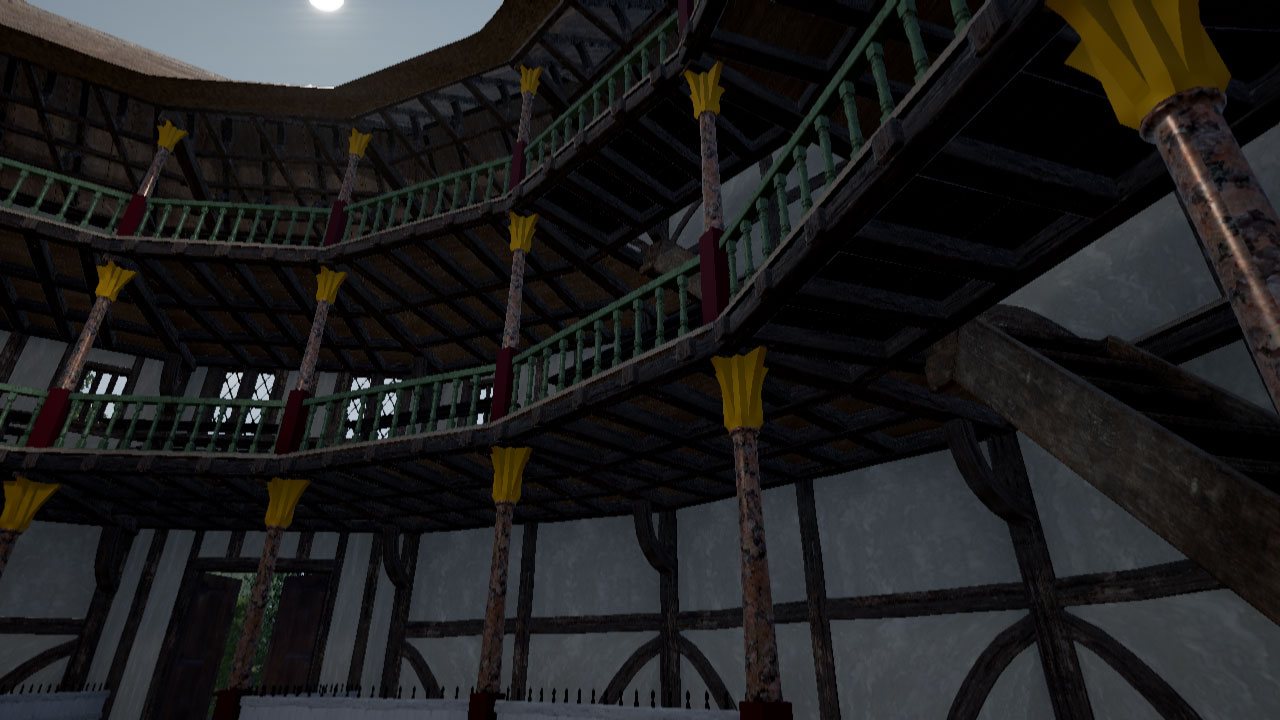

Gabriel Egan, following Greenfield, argues that jutties allowed for a floor-on-floor method of erecting the timber frame, which was far easier and, therefore, a likely choice in construction: ‘in which one wall (presumably the outer) rose in a single plane while the other had jetties so that each storey overhung the one below. The advantage of completing each floor before continuing to the next is lost if there is no jetty and both inner and outer main posts must rise to the full height of the building … it also minimizes the need for overnight propping, reduces the number of joints which must be mated at one time, and provides a convenient working surface (the unnailed floorboards) which can take the place of scaffolding.’75

The model follows Henslowe’s surviving contract for his later Fortune playhouse, which stipulates ‘a jutty forwades in either of the saide twoe upper Stories of ten ynches of lawful assize’. The contract has been read to infer a jutty on both storeys, but may equally be interpreted to mean that one jutty is to carry forwards past both storeys.

[73] Gurr, ‘New Questions about the Rose,’ n.p.

[74] Bowsher and Miller, The Rose and the Globe, 113.

[75] Egan, ‘Reconstructions of the Globe,’ 1–16, who follows the explanation in Greenfield, ‘Timber Framing,’ 106–7.