Lords Room © De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. To view the image using Google Cardboard, click here.

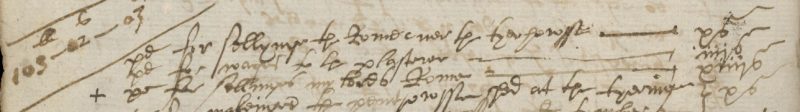

The earliest mention of a ‘Lords Room’ is in Henslowe’s diary in 1592 (MSS VII f.5v), in which he records:

Pd for sellynge the Rome over the tyerhowsse ……….…..xs

Pd for wages to the plasterer………………………….…………iiijs

Pd for sellinges my lords Rome……………………………..….xiiijs

In referring to the ‘my lords Rome [room],’ it is not clear if Henslowe is referring to a room for lords (plural) or for a lord (singular), under whose patronage the company of players performed. In referring to ‘sellynge,’ it is not necessarily clear if Henslowe is referring to ‘ceil,’ as in ‘to line the roof or, provide or construct an inner roof’—i.e., building the ceiling structure (perhaps Henslowe’s outlay ‘for sellinges‘ would seem less equivocal)—or ‘to cover with a line of woodwork [panelling], sometimes of plaster‘— i.e., sealing the structure (OED). In his contract for the Fortune playhouse (fig. 16 [4.2.2]), Henslowe states that the carpenter, Peter Street, ‘shall not be chardged w[i]th … Rendringe the walls w[i]thin Nor seelinge anie more or other rooms then the gentlemens rooms[,] Twoe pennie rooms and stadge,’262 which Egan believes distinguishes between ‘render’ (to apply a lime and sand mortar) and ‘ceil’ in the sense only applicable to having ceilings installed,263 although it is also possible he is referring to panelling the walls and/or the ceiling. In his search through the historical records relating to building practices, Salzman notes several accounts that refer to ceilings constructed from boards of plaster as ‘false roof,’ ‘double roof,’ ‘cilebord’ or instruction ‘to seal the flower [floor].’264 He notes that the custom to ‘seal’ (variously spelled in documents ‘selyng’ and ‘sealing’) refers to panelling a room, often in wainscoting.265 Wooden panelling, which may have been wainscoting, was found in the debris at the remains of the Rose (see fig. 55a).

Just where in the altered playhouse Henslowe’s ‘Lords room’ was is not known. Gurr speculates that it may have been in the middle balcony above to the side of the stage: ‘[a]n angled tiring-house front [at the Rose] would provide a better structure for lord’s rooms over the stage if the central space was for players and the gentry were positioned in the flanking rooms, the angle of which gave at least some view of the stage entrances and the discovery space.’266 This would leave central bay—Henslowe’s ‘Rome over the tyerhowsse’? —for use by players. Gurr’s idea seems in part to be based on the premise, depicted by De Witt in the sketch of the Swan playhouse (fig. 26 [4.4.1]), that the gallery at the back above the stage was used in the open playhouses more generally as a position from which the gentry may observe the players and be seen.

Ernest Rhodes considers the ‘Lords Room’ and the room over the tiring house to be located together on the second gallery tier above the stage, supported by his argument that the third tier would be too high for viewing and that stage level was the province of the gallants and their friends.267

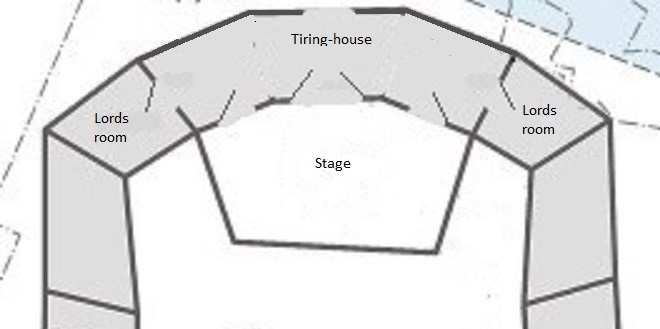

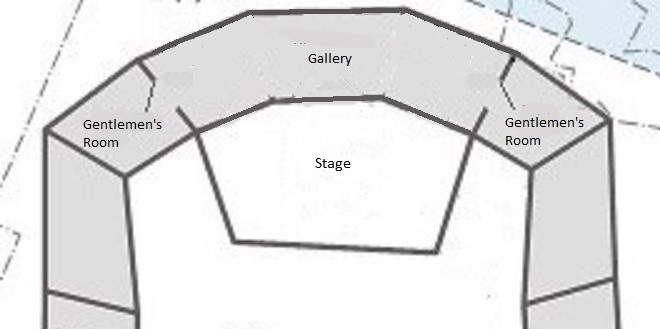

It is certainly conceivable that the central space was divided into three ‘rooms’: the central ‘room’ given over to performance as and when necessary—the space needed for performance wasn’t vast and it seems unlikely the space was dedicated as a music room (see 5.10.3)—and the bays either side made into rooms for spectators, with either one or two dedicated as a ‘Lords room.’ The outer bays at the Rose could conceivably be dedicated to ‘Gentlemen’s rooms,’ giving four rooms in total for the gentry as stated in the Fortune contract. This configuration of Level 1 ‘rooms’ raises problematic questions about access—via ground level isn’t necessarily practical unless room was dedicated to staircases with access from outside to the rear; and coming and going of Lords and Gentlemen via a central staircase rising to the Level 1 gallery would perhaps be inconvenienced by players and the like also needing access. On the plus side, such an arrangement would mean that, rather than dedicated as Lords or Gentlemen’s rooms, the bays either side of the stage could have usefully extended the space in the tiring house (see fig. 82a).

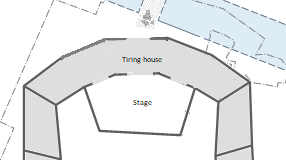

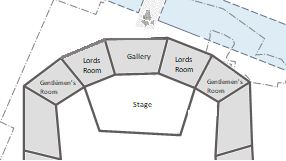

Fig. 82: a. (left) Level 1, showing the new northern half of Phase II dedicated as space for the tiring house; b. (right) Level 2, showing the possible position of rooms for the performance ‘gallery,’ ‘Lords’ and ‘Gentlemen’s’ rooms, although routes of access are left uncertain268

However, Egan concludes that ‘since the fitting of a ceiling to the Lords Room is entered as a separate item of expense [to ‘sellynge the Rome over the tyerhowsse’], the Lords room cannot be in the stage balcony.’269 He argues that ‘the overwhelming evidence [is] that the Lords room could not have been in the stage balcony’ in the public playhouses, and suggests that in his reference to ‘12 penny roome next to the stage,’ Thomas Dekker, in A Gulls Handbooke (1609), is referring to the public playhouses. Dekker refers to ‘the Lords roome (which is now but the stages suburbs).’ Egan argues that the ‘Lords Room’ (available to other patrons for 12 pennies) was positioned ‘in the lowest gallery at the side of the stage,’ and that Jonson’s use of the phrase in Everyman Out of His Humour, ‘over the stage in the Lords room,’ could reasonably be interpreted as the speaker meaning ‘over the other side of the stage’ [i.e., over there] rather than ‘above the stage.’

Egan suggests that ‘perhaps the Lords room might also be referred to as “gentlemen’s rooms”, since a lord is certainly a gentleman even though the reverse is not true. If the two terms referred to different places, it is possible that they formed matched pairs flanking the stage (i.e., one of each on each side), or that the ‘Lords room’ occupied one side whilst the ‘Gentlemen’s rooms’ occupied the other. The currently available evidence does not provide certainty on this matter.’270 Egan’s argument perhaps risks conflating the ‘Lords Room’ with the ‘Gentlemen’s rooms,’ and presumes that both were present at the Rose playhouse, even though the Hope contract only stipulates the gallery but not that it flanks the stage.

Gurr contends that at the Rose the ‘Lord’s rooms’ were evidently distinct from the ‘gentlemen’s rooms’ noted in the Fortune contract and Hope contract; ‘the Gentlemen’s rooms, probably the ones Platter notes as costing an extra penny for a cushion and the best view, were the bays closest to the stage at the lowest level of the galleries, to judge from the Hope contract’s “boxes”.’271

However, Herbert Berry’s discovery of correspondence concerning a quarrel at the Blackfriars between Lord Thurles and Captain Essex in January 1632 confirms that in this indoor theatre at least there were Gentlemen’s, or Lords, ‘rooms’ positioned adjacent to and at the same level as the stage:

This Captaine attending and accompanying my Lady of Essex in a boxe in the playhouse at the blackfryers, the said lord [Thurles] coming upon the stage, stood before them and hindred their sight. Captain Essex told his lo[rd], they had payd for their places as well as hee, and therfore intreated him not to deprive of the benefitt of it. Whereupon the lord stood up yet higher and hindred more their sight. Then Capt. Essex with his hand putt him a little by. The lord then drew his sword and ran full butt at him, though hee missed him, and might have slaine the Countess as well as him.272

Whether the configuration in the private indoor theatres closely mirrored those of the public open playhouses isn’t known. Neither is it known for certain whether in the indoor playhouses the boxes at stage level were repeated immediately above on Level 2, or if multiple ‘boxes’ one above the other were a feature of the open playhouses.

Having the ‘Lords room’ to the side at stage level would certainly provide better sightlines to the discovery space than looking from above. Whilst these playgoers may have benefited from being in a prominent position above the stage, they would be unable to appreciate reveals—reason enough for playwrights to seem to have limited their use of the discovery space, he suggests.273

Rhodes points out that the cost of the work undertaken suggests that ‘the work was extensive, costing Henslowe twenty-eight shillings—equal to wages paid to one man for about 28-days of work.’274

That two rooms were intended for use by Lords and other gentlemen is suggested by William Empson because of Henslowe’s use of plural for ‘sellinges’ (i.e., ceilings),275 despite ‘Rome’ (i.e., room) being singular.

In the model, Henslowe’s ‘Lords Room’ could refer to one of the ‘Gentlemen’s room’ in the lowest gallery, although two rooms either side of the stage have been made fit for a Lord patron and others to occupy. The entrance to these two rooms is through doors from the tiring house.

Fig. 83: a. (left) Level 1 tiring house with flanking ‘Gentlemen’s’ rooms; b. (right) Level 2 gallery and flanking ‘Gentlemen’s rooms’ or ‘Lords rooms’276

Following Henslowe’s expenditure, in the Phase II model these rooms have plaster ceilings. Taking note of the debris found at the site of the Rose, the side walls have been covered in wood panelling/wainscoting with the occasional carved rose motif.

Fig. 84: Sixteenth-century English oak panels carved with rose

The rooms would have been elaborately painted, perhaps similar to the images found in the painted staircase at Knole House in Sevenoaks, Kent (1605).

Fig.85: The staircase at Knole House in Sevenoaks, Kent (1605)

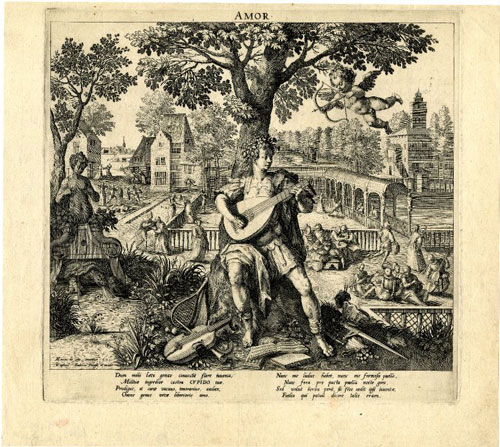

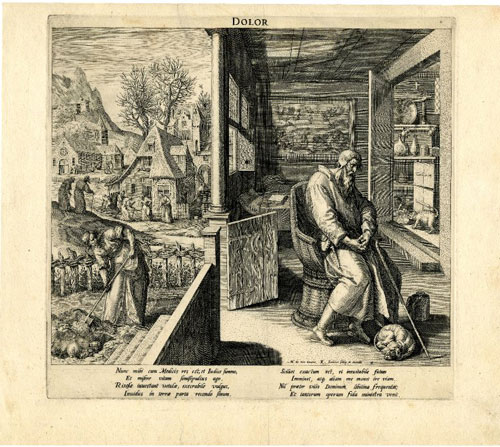

Following the Knole staircase, the back wall of each room is plastered and painted with a decorative arched frame and pillars. Within each oblong frame are images from ‘The Four Temperaments’ and ‘The Four Ages of Man’ by Maarten de Vos, painted in a sepia.

Fig. 85: a. (left) Cholericus; b. (right) Sanguineus (painted onto the walls of Room 1, left of the stage) © Trustees of the British Museum

Fig: 86: c. (left) Amor; d. (right) Dolor (painted onto the walls of Room 2, right of the stage) © Trustees of the British Museum

The ceilings of each room are plastered simply. The wooden doors match the panelling. The seating consists of four forms (benches) with cushions.277

[262] Foakes, Henslowe’s Diary, 308 (Muniment 22).

[263] Gabriel Egan, ‘The Situation of the Lord’s Room: A Revaluation,’ Review of English Studies, vol. 48 (1997), 297–309.

[264] Salzman, Building in England Down to 1540, 214.

[265] Ibid, 258.

[266] Gurr, ‘The Bare Island,’ 38.

[267] Rhodes, Henslowe’s Rose, 71.

[268] Adaptation of original image in Bowsher and Miller, The Rose and the Globe, 125.

[269] Egan, ‘The Situation of the Lord’s Room,’ 297–309.

[270] Ibid.

[271] Ibid, 38.

[272] Herbert Berry, ‘The Stage and Boxes at Blackfriars,’ Studies in Philology 63 (1966), 165.

[273] Gurr, ‘The Bare Island,’ 38.

[274] Rhodes, Henslowe’s Rose, 71.

[275] William Empson, Essays on Shakespeare (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994 [1986]), 168

[276] Adaptation of original image in Bowsher and Miller, The Rose and the Globe, 125.

[277] Research into furniture for the Gentlemen’s rooms at the reconstructed Globe on London’s Southbank concluded that there was no evidence to suggest that individual chairs would have been used in the open playhouse to accommodate richer or more distinguished spectators. Here, as at the Globe, short two-person forms (benches) have been used for seating in the Gentlemen’s and ‘Lords room’. (Anon., ‘Finishing the Globe: To Paint or Not to Paint,’ Shakespeare’s Globe Online Discovery Space – Research Papers: https://www.shakespearesglobe.com/learn/research-and-collections/research-resources/ )