There is not much information about seating from either archaeological or documentary sources.

Sir William Davenant’s prologue in The Unfortunate Lovers (1643 [1638]), performed at the private Blackfriars, speaks of the citizenry in the two-penny galleries of an earlier generation who, attending the public playhouses twenty years before (my emphasis):

…to th’ Theatre would come

Ere they had din’d to take the best room;

Then sit on benches,not adorned with mats,

A graciously did veil the high-crowned hats

To every half-dress’d Player, as he still,

Through th’hangings peep’d to see how th’house did fill.

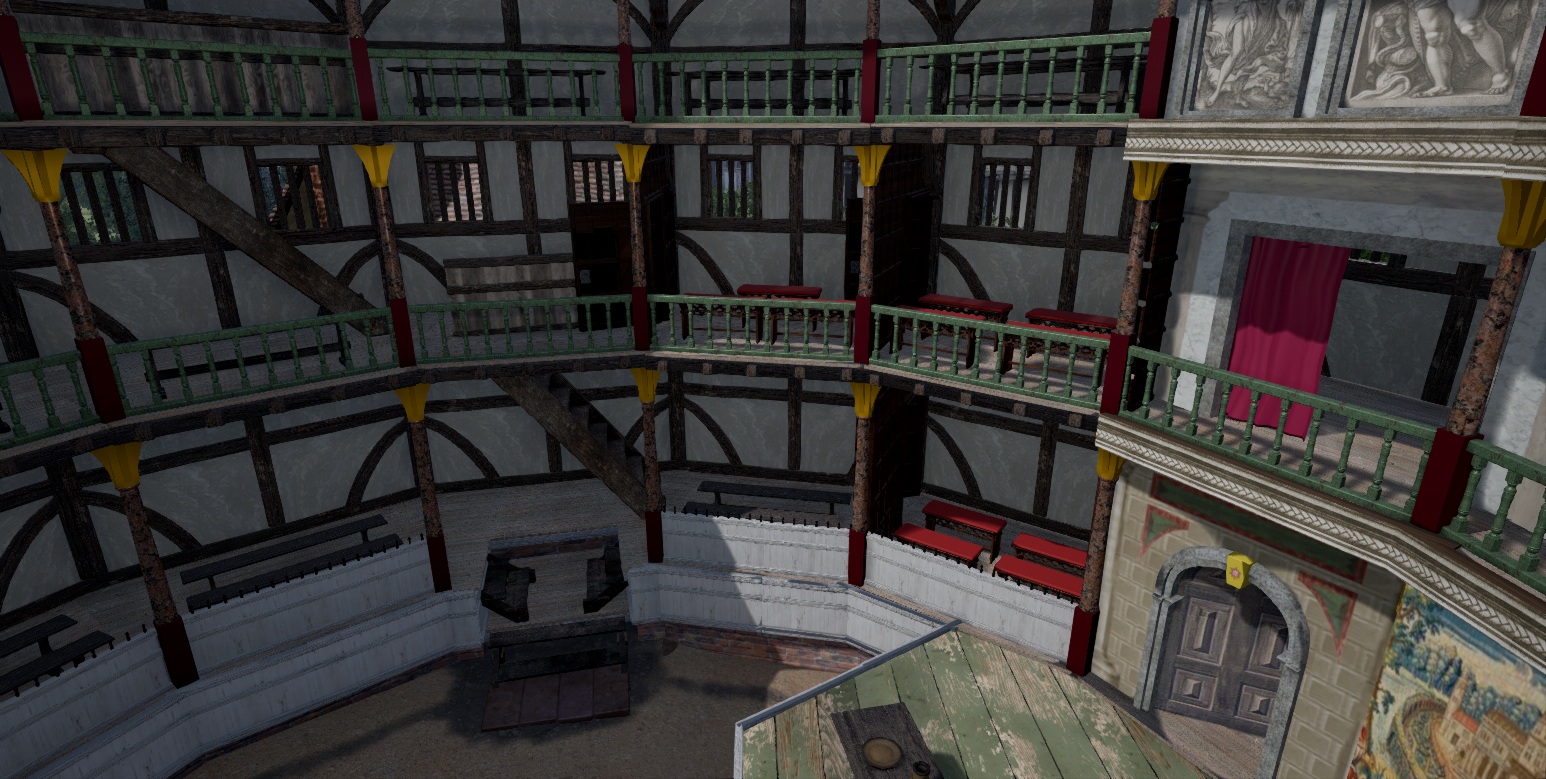

It isn’t clear if benches here refer to seating made up of single forms, as given in the 3D model of the Theatre, Shoreditch (1576–1598), by MOLA/Cloak and Dagger Studios (fig. 47), or refers to tiers of seating suggested, perhaps, by the illustration of the Swan playhouse, c. 1596 (see fig. 26 [4.4.1]) and given in the illustration by William Dudley (see fig. 15 [4.2.2]).

© MOLA/Cloak and Dagger Studios114

playhouse, c. 1596 (see fig. 26 [4.4.1]),

showing what appear to be tiers of

seats or ‘degrees’ and which resemble

the ‘steps’ into the galleries

Antimo Galli, a Florentine reporting home, refers to such audience arrangements in his report on his visit to the Curtain playhouse in August 1613, describes how one could pay to ‘go into one of the little rooms, to ‘sit in the degrees that are there,’ or for ‘standing in the middle down below.’115 If such degrees were designed into the Rose they were probably built from floor levels within the galleries rather from the ground surface, for no evidence of supports, or ‘needles,’ were found to have left traces in the clay surface under the lower gallery floor.116 Henslowe’s Fortune contract and Hope contract imply secondary elements like seating were made from cheaper and easier-to-work imported softwoods generally referred to as Baltic fir, commonly available in London in standard sixes.117

William Lambarde described the possibility of paying a penny to enter the yard, a second penny to enter the scaffold (galleries), and a third penny ‘for a quiet standing.’118

Platter records that in certain locations in the galleries ‘the seating is better and more comfortable and therefore more expensive. For whoever cares to stand below only pays one English penny, but if he wishes to sit he enters by another door, and pays another penny, while if he desires to sit in the most comfortable seats which are cushioned, where he not only sees everything well, but can also be seen, then he pays yet another English penny at another door.’119

Conjectured heights of the lower and second-tier gallery at the Rose suggest sufficient sightlines for a seated audience. Seating in a third gallery was more problematic because of ‘compromised’ sightlines.120

Tiffany Stern (cited in Egan) argues that the galleries are where spectators would expect to stand and walk rather than to sit, and points out that the label ‘porticus’ attached to the top most gallery in the sketch of the Swan playhouse is the Latin word for a covered walkway; and in a draft lease for the Theatre (1576), Burbage indicates that spectators could sit or stand in the galleries.121 We might reasonably speculate that this was true for the Rose, dated between the Theatre and the Swan.122

In the completed model, it was decided not to include seating ‘degrees’ (the image below shows how these may have looked) but instead to provide a combination of forms (benches) and room for standing.

A spectator may therefore pay a penny to enter and stand in the yard; or pay a second penny to enter the Level 1, 2 or 3 galleries to sit or stand ; or pay a third penny to enter a private room (Level 1 and 2) for quiet standing or to sit on a two-seater stool with a cushion (fig. 49), closest to the stage.

The remaining two-penny bays have 4 or 5 forms (benches), with room for standing and walking around the gallery behind. In the upper (Level 3) gallery, the bays have two forms (benches) in each, again with room for standing allowing patrons to push forwards to the balcony for better viewing.

Andrew Gurr and James Orrell calculate that ‘the internal depth [of the galleries at the Rose] was about 10ft 6 ins, and the average length of the benches in them was about 13 ft. Using the Elizabethan standard separation of 18 ins fore-and-aft, it would appear that there were at least six benches in each gallery bay … giving a total gallery capacity of 1404 persons.’123 Their calculation seems not to give room to those standing, however.

[114] Cloak and Dagger Ltd., with Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA): https://www.mola.org.uk/blog/step-inside-shakespeares-first-theatre [accessed 22 July 2017].

[115] John Orrell, ‘The London Stage in the Florentine Correspondence, 1604–1618,’ TRI 3 (1977–8), 171.

[116] Bowsher and Miller, The Rose and the Globe, 115.

[117] Greenfield, ‘Timber Framing,’ 107.

[118] Chambers, The Elizabethan Stage, II, 359.

[119] See Platter, Travels in England 1599, 167.

[120] Greenfield, ‘Reconstructing the Rose,’ 31ff.

[121] Egan, ‘The Theatre in Shoreditch, 1576–1599,’ 168–85, citing Tiffany Stern, ‘”You That Walk I’th Galleries”: Standing and Walking in the Galleries of the Globe Theatre,’ Shakespeare Quarterly 51, (2000), 211–16.

[122] Of course, if we’ve learnt anything from the recent discoveries of the Theatre, the Rose, the Curtain, and the Fortune playhouses, the excavated remains suggest that each was different and that the idea that there was a chronological pattern of evolution from one building to the next isn’t borne out by the archaeology.

[123] Andrew Gurr and James Orrell, ‘What the Rose can tell us,’ Antiquity 63:240 (September 1989), 428.