Evidence seems to suggest that three storeys were common for playhouses. Circa 1585, Samuel Kiechel, a German merchant visiting London, records the two playhouses in Shoreditch to the north, ‘are so made as to have about three galleries over one another.’66

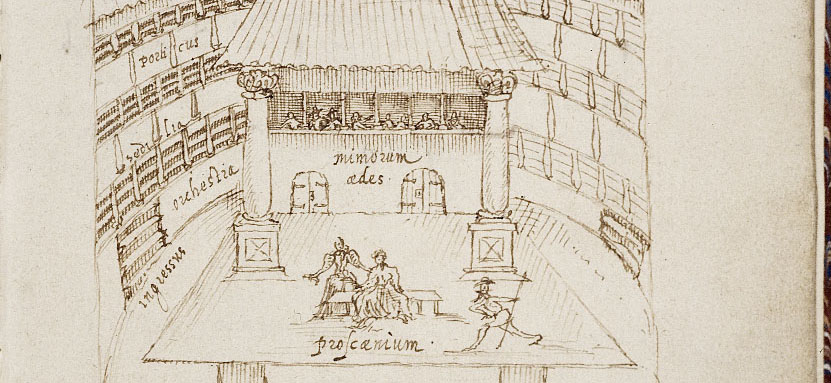

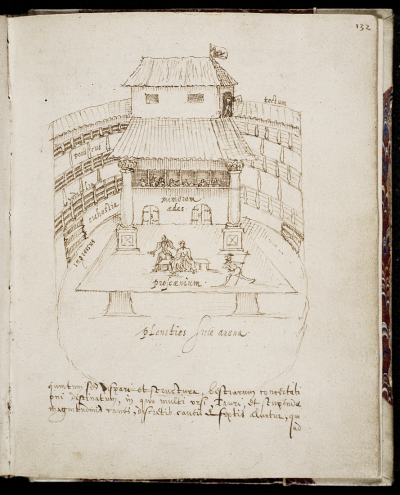

The sketch of the interior of the Swan playhouse made by Arnoldus Buchelius, after the sketch sent to him by his friend Johannes de Witt, also shows three galleries (fig. 26).

Henslowe’s Hope playhouse, modelled on the Swan, also had three tiers of galleries.67

Henslowe’s Fortune contract (fig. 16 [4.2.2]) stipulates ‘the saide fframe to conteine Three Stories,’ as well as the relative heights and widths of its three tiers: ‘in heighth The first or lower Storie to Conteeine Twelue foote of lawfull assize in heighth The second Storie Eleaven foote of lawfull assize in heighth And the Third or vpper Stprie to conteine Nyne foote of lawfull assize in height / All of which Stories shall conteine Twelue foote and a half of lawfull assize in breadth througheoute.’ 68

However, in seeming contradiction, Greenfield suggests that the Rose playhouse may have had only two galleries. He argues that Norden’s depiction of the Rose playhouse is ‘shown considerably smaller than would be expected for a three storey building in relation to the surrounding buildings, and the other playhouses,’ and that the distance of the drip line cut into the yard from the timber frame may suggest only two storeys (see 4.4.2). Greenfield’s conclusion is that a three-storey Rose playhouse would have had ‘compromised’ sightlines from the upper most gallery—something which may not have been of concern to playgoers in the sixteenth century.69 The models allow us to test this hypothesis: playgoers standing on a third-tier (Level 3) gallery at both Phase I and II playhouse appear to have been able to see the stage uncompromised (see 4.13.2 and 5.11 respectively).

The model uses the Fortune contract dimensions for the height of lower, middle and upper galleries—12ft, 11ft, and 9ft respectively—measured from one floor level to the next floor level (rather than floor to ceiling).

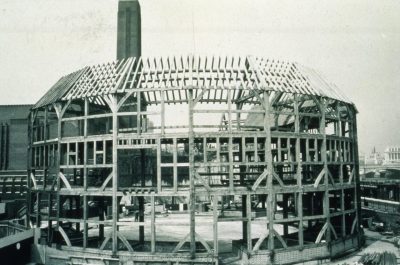

Greenfield thinks it likely that the galleries were supported by timber crossbeams. The positioning of internal bracing to counteract the effect of wind and people using the galleries is not known from the available evidence. Experiments during the reconstruction of Shakespeare’s Globe theatre in London (fig. 27) suggested they are best positioned on the cross frames from outer to inner wall and in the upper two corners and above head height so as not to inconvenience sightlines through the open inner frame. Rigidity in the front open bays is provided by balustrades. Braces prevent the rectangular frame distorting into a parallelogram under the load, accompanied by a flat floor. The model follows the decision at the reconstructed Globe to give the braces a slight concave curve, which were coming into fashion in the early seventeenth century.70

A wooden baluster was found in the debris of the northern boundary ditch (fig. 28), although it is not clear exactly where it belonged or from which phase of the building of the Rose it came from, if at all. Henslowe’s purchase of ‘ij [two] dossen turned ballysters [balusters]’ for his alterations to the playhouse in 1591/2, during which the northern part of the galleries were pulled down and extended, was perhaps to furnish the new gallery fronts to match the old.

with turned wooden uprights also painted to resemble marble pillars

In the model, balustrades have been added to the fronts of the second- and third-tier galleries and painted. A surviving example can be found at Queen’s House in Greenwich (c. 1630s), where the Great Hall oak balcony balustrade has been painted to look like green marble (fig. 29).It should be noted, however, that the balustrade found at the Rose showed no surviving traces of pigment.

The model follows the evidence that the fronts of the lower gallery in some of London’s playhouses were boarded, as shown in the sketch of the Swan (fig. 26) and specified in the contract for Henslowe’s later Fortune playhouse (fig. 16 [4.2.2]): ‘The same Stadge to be paled in belowe with good stronge and sufficyent newe oken bourdes And likewise the lower Storie of the saide fframe w[i]th inside, and the same lower storie to be alsoe laide over and fenced wth stronge yron [iron] pykes,’71 perhaps a deterrent to playgoers climbing over into the galleries to avoid paying a penny to enter, or to keep different sections of playgoers apart, or both. It is possible such ‘stronge yron pykes’ ran around the stage, too: the indoor stages depicted on the title-pages of William Alabaster’s Latin play Roxana Tragaedia (1632 [c. 1592]) and Nathanael Richards’ Messalina (1640 [c. 1635]) show a low rail running around the edge presumably as a barrier between player and spectator.72

[66] Chambers, The Elizabethan Stage, II, 358.

[67] Greg, Henslowe Papers, 19–22.

[68] Foakes, Henslowe’s Diary, 307 (Muniment 22).

[69] Greenfield, ‘Reconstructing the Rose,’ 31ff.

[70] See Greenfield, ‘Timber Framing,’ 110–11.

[71] Foakes, Henslowe’s Diary, 307 (Muniment 22).

[72] William Alabaster, Roxana Tragaedia (London: William Jones, 1632), STC 2nd 250; Nathanael Richards, The Tragedy of Messallina, the Roman Emperesse (London: Daniel Frere, 1640), STC 2nd 21011.