As with Phase I, regular use was certainly made in the redesigned Rose playhouse of the acting space over the stage, what Henslowe refers to as ‘the Rome [room] over the tyerhowsse.’

Of the plays considered to be written for or staged at the post-1591/2 Rose, a number give explicit or implicit directions for acting ‘above’ the stage:369

In Old Fortunatus, the dialogue indicates that a pair of stocks is located above the stage: ‘Drag him to yonder towre, there shackle him, / And in a paire of Stockes, locke vp his heeles.’370 Two men are taken at different times and placed in them, seen by the audience.

In The Death of Robert Earl of Huntington, a window is used in a place above the stage to discover a Senecan tableau.371 Further stage directions instruct: ‘Exuent from above’ and ‘Enter Bruse, upon the walles’; and later the King says of Bruce, ‘see this traitour pearcht / Upon the castles battements so proud; come downe.’372

In Thomas Heywood’s A Woman Killed with Kindness (1607 [1603]), a stage direction reads ‘Enter over the stage Frankford, Anne and Nicholas’ (sc. 5). Wendoll, already on stage, sees them (‘There goes thou’), but they do not see him. It is possible, however, that the stage direction is ambiguous and may refer to the characters entering from one door and a passing over the stage to exit from the other, with Wendoll standing aloof.’373

In The Brazen Age, stage directions give ‘Enter upon the wals’ and, later, ‘All the Gods appeare above.’374

Other plays call for one or two performers to play ‘above on the walls,’ ‘upon the walls,’ ‘on the turrets,’ ‘a gallery,’ ‘above at the window,’ ‘this window,’ ‘in the window.’ No depth is required for one or two people performing, and most speak from the balcony to someone on the stage.

A few plays thought to have been staged at the post-1591/2 Rose require extended acting ‘above’ with between three and five characters, or unspecified numbers (senators, a royal train, etc.), including action.

In Henry VI, Part I, soldiers scale the walls and force the French to ‘leap o’er the walles.’375

In Christopher Marlowe’s Massacre at Paris (1596? [1593]), terrorists break into the Admiral’s bedroom (above), murder him, and pitch his corpse ‘down’.376

In Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great, Part II (1590 [1594-95]), 5.1., forces ‘scale the walles’ and one characters is hung ‘in chaines on the citie walles.’377

In Titus Andronicus (Q1594; 5:1), Titus ‘opens his studie doore,’ and speaks to Tomara below, who beckons ’Come downe and welcome me.’378

In Englishmen for my Money, one character is hoisted ‘up’ in a basket.379 Where people lay siege to the walls (‘they scale the walls’) scaling them is probably effected by using ladders, as in William Shakespeare’s Henry V.380

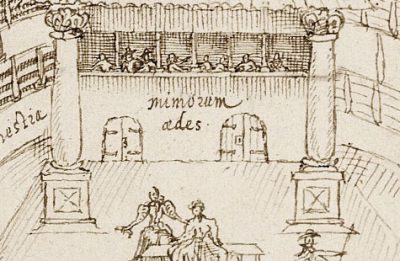

Whether the gallery at the Rose playhouse was used for spectating as depicted in the sketch of the Swan (fig. 105) can only be speculated.

In the model of Phase I the first level is relatively open and the stairs in the tiring house closed off with a curtain. However, in the model of Phase II the room ‘over the tyerhouse’ is separated from the access stairs behind by a wall. A green curtain is hung on a rail behind the opening so that it can be closed off when necessary.

It isn’t known if the gallery at the Rose was used as a dedicated music room, although Richard Hosley thinks it unlikely. He argues that ‘in the majority of cases stage-directions call for music to be performed “within” and not above, and certainly not before 1598’. In the vast majority of instances, he continues, ‘”within” bears the meaning “out of sight of the audience on the stage level of the tiring house”.’ The few notable exceptions in Rose plays that exist—for example Henry VI, Part I, a Rose play, which gives ‘Enter…within, Pucell, Charles, Bastard, and Reigneir on the Walls,’ where within clearly indicates ‘above’—are not in relation to music.381

Hosley argues that unlike the indoor theatres, where inter-act music was played in a music room ‘above’ where they could be heard even when playing softly, in the public playhouses music was often ‘military’ in style: ‘sometimes performed on stage but in any case loud enough to be performed also behind the tiring-house façade (“within”); and often it was an accompaniment for songs or a special effect of some sort, in which case it might be performed on stage, or within the tiring-house behind an “arras” fitted up in front of an open doorway, or even in particular circumstances under the stage.’382

He concludes that, ‘since the special requirements of inter-act music did not exist in the public theatres before 1604, those theatres did not develop music-rooms before that date.’ It seems unlikely, according to Hosley’s analysis, that the Rose had a dedicated music room for either Phase I or II. That’s not to say the gallery space at the Rose didn’t at least provided an opportune space for musicians to occupy, particularly given the cramped conditions of the tiring house. As Hosley argues with reference to the first Globe playhouse, the only adaptation necessary to convert the ‘Room over the tyrehouse’ to a music room would have been to fit it up with hangings ‘in order to comply with the custom of concealing the musicians during the action of the play.’383

Gallery, or room over the tiring house, Phase II © De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. To view the image using Google Cardboard, click here.

In the model, the central gallery bay is a large squared opening with a cantilevered balcony projecting over the stage. The addition in 1595 of a ‘throne in the hevens’ may have lowered a chair to the stage or, as given here, to come to rest on the balcony: a stage direction in the 1599 edition of A Looking Glass for London and England, performed at the Rose, gives ‘Enters bought in by an Angell Oseas the Prophet, and set downe over the Stage’ (my emphasis).384 If the direction does indeed refer to a throne descending, the preposition may indicate either the location from where the throne descends or that it eventually comes to rest ‘above’ the stage, i.e., on the balcony. (Egan notes that ‘Glynne Wickham argues—not entirely convincingly—that “set downe over” here merely means “placed upon”’, to suggest that a throne is simply brought on stage from the tiring house.385) If, as here, the heavens trap was in the gable and not located in a hut above the stage as some has postulated, ‘over’ may well refer to ‘above the stage.’ That a throne should come to rest mid-way between heaven and earth would be symbolically fitting of the divine right of the monarch.

The bays to either side are double arched, following a similar design for the hall screen for Worksop Manor (see fig. 58 [4.11.1]).

A painted balustrade runs the length of the gallery and the cantilevered balcony.

The front is painted to match the colouring of the frons scenae at stage level.

Painted in grisaille on the wall at either end are depictions by Hendrik Goltzius (c. 1592) of the Roman god Marcurius [Mercury] and Sol [Apollo], the gods of poetry and eloquence, from the series ‘Eight Deities’ (see fig. 67 [4.13.2]).

On the back wall, painted in grey/grisaille are depictions of the dramatic muses by Virgil Solis (1562),386 from left to right Thalia (comedy), Calliope (epic poetry), Terpsichore (dance), and Melpomene (tragedy), who mediated between the Gods and the earth (fig. 106).

Fig. 106: The Muses by Virgil Solis

The columns and decoration have been adapted from the Worksop Hall Screen.

[369] Gurr, ‘The Rose repertory,’ 119–34; McMillin, The Elizabethan Theatre, 115ff; Rhodes, Henslowe’s Rose, 185ff.

[370] Dekker, The Pleasant Comedie of Old Fortunatus, Sig. K3r.

[371] Rhodes, Henslowe’s Rose, 85-86. Munday and Chettle, The Death of Robert Earl of Huntington, Sig. J2r, gives ‘In a thick wall he a wide windowe makes’, where later the tableaux appears above the stage (Sig. L4r); before descending to the gates of the castle, Bruce goes to where his dead mother and brother sit and, having kissed her, goes to the gates. Seven lines later he emerges onto the stage.

[372] Munday and Chettle, The Death of Robert Earl of Huntington, Sig. I2r, L1r and L2r.

[373] Thomas Heywood, A Woman Kilde with Kindness (London: William Jaggard, 1607). STC 2nd 13371. Henslowe records four payments to Thomas Heywood for the play in February and March 1603 for Worcester’s Men who were playing at the Rose. (Foakes, Henslowe’s Diary, 223–25.)

[374] Thomas Heywood, The Brazen Age (London: Nicholas Oakes, 1613), Sig. H1r and I3r (STC 2nd 13310).

[375] Shakespeare, Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies, 455.

[376] Christopher Marlowe, The Massacre at Paris : with the Death of the Duke of Guise (London: E.A. for Edward White, [1596?]), Sig. B1r (STC 2nd 17423), whose tile page states ‘as it was played by the right honourable the Lord high Admirall his servants’. Henslowe records a performance of a play titled The Tragedy of the Guise (‘gvyes’), thought to be Marlowe’s play, on 26 January 1593 performed by Lord Strange’s Men at the Rose; Admiral’s Men performed the same play a number of times between June and September 1594 (Foakes, Henslowe’s Diary, 20, 22–24). If and how a body was ‘pitched down’ on the Elizabethan stage isn’t known, but may have been represented in ways other than acted out.

[377] Christopher Marlowe, Tamburlaine the Great, The Second Part of the bloody Conquests of mighty Tamburlaine (London: Richard Jones, 1590), Sig. K3r, K3v (STC 2nd 17425); Henslowe’s ‘Diary’ records performances [of ‘the 2 pte tamberlen’] between December 1594 and November 1595 by the Admiral’s Men, presumably at the Rose (Foakes, Henslowe’s Diary, 26–29, 33); Henslowe’s inventories of props and costumes for the Lord Admiral’s Men at the Rose on 10 and 13 March 1598 (reproduced by Foakes, 320–21) includes and ‘Tamberlynes cotte [coat] with coper lace’ and ‘Tamberlyne brydell,’ which ‘presumably the sort of muzzle employed in the last act of Tamburlaine, Part II’ (Jonathan G. Harris and Natasha Korda, eds., Staged Properties in Early Modern English Drama (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 100).

[378] William Shakespeare, The Most Lamentable Romaine Tragedie of Titus Andronicus (London: John Danter, 1594), Sig. I3r (STC 2nd 22328). Henslowe records the first performance on 23 January by Sussex Men presumably at the Rose; he records further performances by the Admiral’s Men until 12 June 1594 (Foakes, Henslowe’s Diary, 21–22). The play was first published in quarto in 1594, and states on its title page ‘As if was plaide by the Right Honourable the Earl of Darbie [Derby], Earle of Pembrooke, and Earle of Sussex their servants’, who were playing at the Rose.

[379] Haughton, English-Men For my Money, Sig. G3r. 380 Gurr in ‘The Rose repertory,’ 128.

[380] Gurr, ‘The Rose repertory,’ 128.

[381] Richard Hosley, ‘Was there a music-room at Shakespeare’s Globe?,’ Shakespeare Survey 13 (1960), 116.

[382] Ibid, 117.

[383] Ibid, 118.

[384] Lodge and Greene, A Looking Glasse for London and England, Sig. B1r.

[385] Egan, ‘The Theatre in Shoreditch, 1576–1599,’ 168–85, citing Glynne Wickham, ‘“Heavens”, Machinery, and pillars in the Theatre and other early playhouses,’ in The First Public Playhouse: The Theatre in Shoreditch, 1576–1598, ed. Herbert Berry (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1979), 8.

[386] Virgil Solis (1514-1562), The Nine Muses (1562), Université de Liège, Belgium: https://www.wittert.ulg.ac.be/fr/flori/opera/solis/solis_muses.html